As part of the Regimental Museums Project, Dr Andrew Hillier explores photographs reflecting the short but significant contribution of the 1st Chinese Regiment to Britain’s military presence in China.

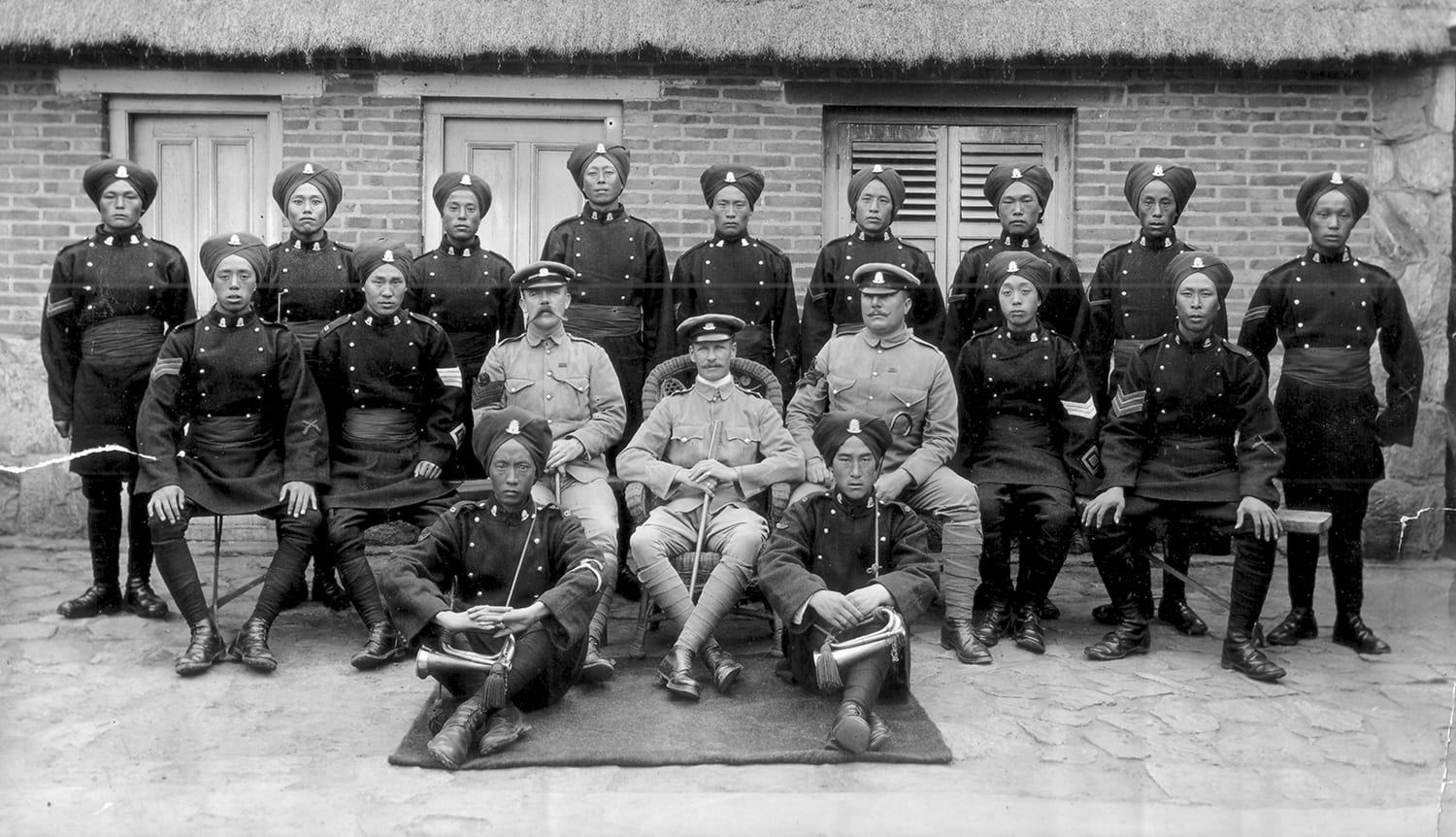

Raised in 1898 to protect the Royal Navy’s newly-acquired deep-water base at Weihaiwei (Weihai) against foreign incursion, within two years, soldiers of the 1st Chinese Regiment were engaged against their own people in the Boxer Uprising (1900). Whilst Major Arthur Barnes (Wiltshire Regiment) would maintain that it ‘more than fulfilled the high hopes formed by its officers, and by those in high military authority’, it never saw active service again and was disbanded six years later on the grounds that it was an unnecessary extravagance.[1] Nonetheless, its history forms an important aspect of the British military presence in China, entailing, as it did, British officers and NCOs raising and commanding a regiment comprising exclusively Chinese rank and file. Although there was a precedent in the formation of the Canton Coolie Corps during the Second Opium War and an excellent relationship would be forged between officers and men, there were inherent ambiguities in Chinese subjects serving in a British regiment. These are well-reflected in the rich collection of photographs and other material that can be found in a number of regimental museums and other public archives.

1. 1st Battalion, Chinese Regiment – British and Chinese Non-Commissioned Officers of Number Eight Company in China 1898-1903, SBYRW: 40220. © The Rifles Berkshire and Wiltshire Museum. In the centre is Major (as he later became) Arthur Barnes (Duke of Edinburgh’s Wiltshire Regiment).

From the outset, the Chinese government objected to Chinese subjects being enlisted and, as a compromise, the British government initially agreed that they would only be deployed on defensive duties relating to the naval base.[2] However, this seems to have been quickly forgotten, and when it came to the Boxer Uprising the following year, at least one third of the men deserted. According to British military intelligence, this was because they did not want to fight against their fellow-countrymen or there had been threats against them and their families by alleged Boxer sympathisers.[3]

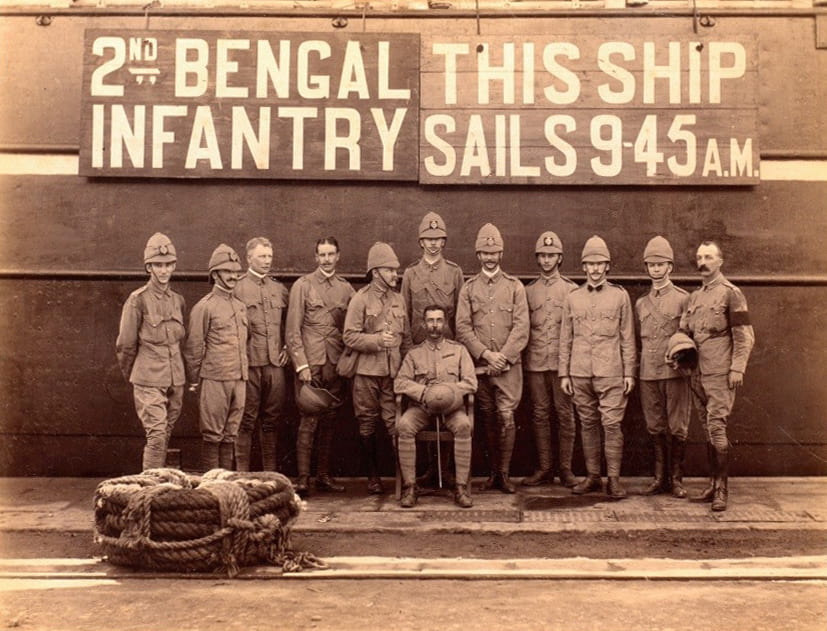

2. ‘Leaving Bombay’, NAM 1965-10-214-89, © National Army Museum. From an album of 203 photographs compiled by Colonel Anson Hugh McCleverty (as he became), 2nd Queen Victoria’s Own Rajput Light Infantry. Assigned to the 1st Chinese Regiment, McCleverty, fourth from right, took a large number of photographs of Weihai and the surrounding area. Returning to his regiment, he was later appointed one of its official photographers.

3. Soldiers of the 1st Chinese Regiment parade in field dress, NAM 1965-10-214-89, 1900, © National Army Museum. From an album of 203 photographs compiled by Colonel A. H. McCleverty, this one possibly taken by him. Many of the recruits were farmers who were trained from scratch.

It is unclear how officers were selected for assignment to the Regiment save that the War Office stipulated they should all be of high calibre. Drawn from some ten regiments in the early stages, the Duke of Wellington’s Own West Riding Regiment was particularly well- represented, providing three officers – Major C.D. Bruce, Captain W.M. Watson and Lieutenant Bray, all of whom subsequently rose to the rank of Brigadier-General- and one NCO, Sergeant Brook.

In July 1900, twenty-two British officers and 363 Chinese other ranks took part in the relief of Tianjin under the overall command of General Dorward (Royal Engineers).[4] After eighteen days of intense fighting, it was the only British Army regiment to be engaged in the final assault, in which both officers and men distinguished themselves.

4. Members of the 3rd Battalion, 60th Royal Rifle Corps, thought to be Colour Sergeant English, Sergeant Payne, Sergeant Jacques and one other; downloaded from http://rgjmuseum.co.uk/photo-archive-item/rifle-brigade-china/ (170A12W/P/2324); see also the Hampshire Council Archives http://www3.hants.gov.uk/archives/visiting-hals.htm 170A12W/P/2321-2331. According to the Rifle Brigade Chronicle, when Payne and Jacques, and Riflemen, Hayward and Robertson, left in the summer of 1901, they were given ‘splendid reports’ and, it continued, ‘Colour Sergeant English is still out there upholding the credit of the regiment as an instructor of Chinamen. He is certain to do it well.’

Of the thirteen Distinguished Conduct Medals awarded in the whole campaign, the Regiment received three of them – Colour Sergeant Purdon, Quartermaster Sergeant E. Brook, and Sergeant Gi-Dien-Kwee, for ‘his command of a half-company without any European’ during the advance, and who may have been the first Chinese national to be so decorated and would certainly not be the last.[5] Attended by his interpreter, ‘the faithful Liu’, and his bugler, Li Ping- chen, Barnes was full of praise for the men’s ‘cold-blooded courage and stamina’, which included ‘escorting heavy guns over broken and swampy country’.

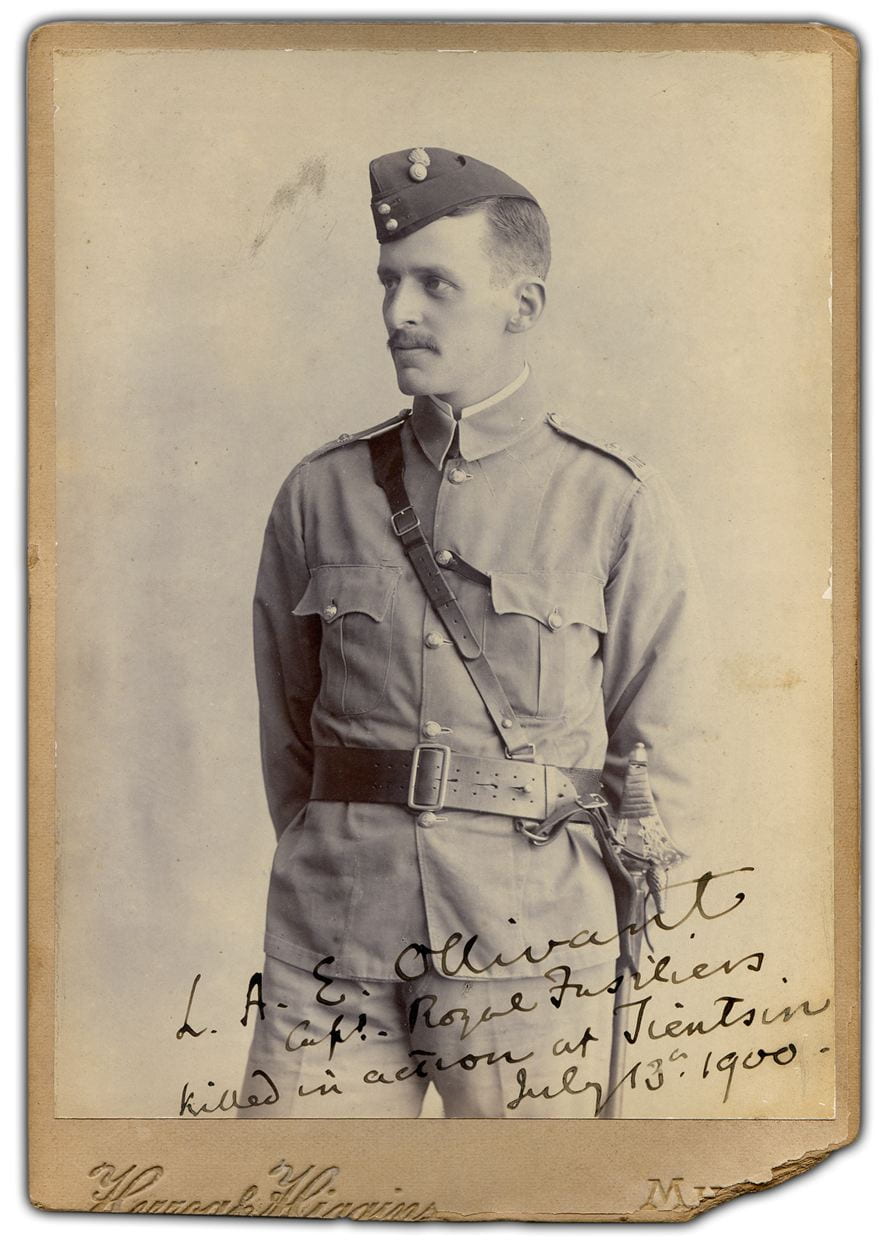

5. Captain Ollivant, Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment). Photographer, Herzog & Higgins, Mhow, India, c. 1899.

However, it was Captain Ollivant who, in Barnes’ words, performed ‘one of the bravest acts amongst many’. Instructed to take extra munitions to the U.S infantry, ‘the Fates were against him and he had only gone a few steps when he was shot through the head … We laid him quietly to rest the next day, in the little cemetery near the Recreation Ground’. ‘His loss’, continued Barnes, ‘was very keenly felt by us all, for his genial good heart and his cheery, never-failing sweetness of disposition had endeared him to us all.’[6]

6. The cap badge worn by Captain (later, Brigadier-General) W. Milward Watson (Duke of Wellington’s Own West Riding Regiment) 1900-1903 NAM. 1964-12-44-1. © NAM

Thus was the Regiment’s esprit de corps forged and, in recognition of its valour, it was authorised to wear a representation of Tianjin’s city gate as its cap badge. Keen to repeat the performance, it prepared for the march and relief of Peking. In this, however, it would be disappointed, as we shall see in the next post.