Brian Dott received a Master’s degree in Chinese Studies from the University of Michigan and his PhD in Chinese History from the University of Pittsburgh. He teaches in the History Department and Asian & Middle Eastern Studies Program at Whitman College. His passion is studying changes in Chinese cultural practices from 1500 to the present. Brian R. Dott is author of The Chile Pepper in China A Cultural Biography‘ (Columbia University Press, 2020). His previous book examines different groups of pilgrims to one of China’s most sacred mountains: Identity Reflections: Pilgrimages to Mount Tai in Late Imperial China (Harvard University Asia Center, 2004).

Brian Dott received a Master’s degree in Chinese Studies from the University of Michigan and his PhD in Chinese History from the University of Pittsburgh. He teaches in the History Department and Asian & Middle Eastern Studies Program at Whitman College. His passion is studying changes in Chinese cultural practices from 1500 to the present. Brian R. Dott is author of The Chile Pepper in China A Cultural Biography‘ (Columbia University Press, 2020). His previous book examines different groups of pilgrims to one of China’s most sacred mountains: Identity Reflections: Pilgrimages to Mount Tai in Late Imperial China (Harvard University Asia Center, 2004).

Chile peppers (also spelled chilli or chili) first arrived in China from the Americas around 1570. Their popularity took off quickly. A source from 1621 described them as being grown everywhere and important for cooking and medicine. Ultimately, the Chinese use of chile peppers has influenced a wide range of cultural practices, from cuisine to medicine, from decorations to gender tropes. I began this project with a simple question; I was eating in a Sichuan restaurant in Beijing and wondered how the Chinese had begun eating something new with such a strong and distinctive flavour?

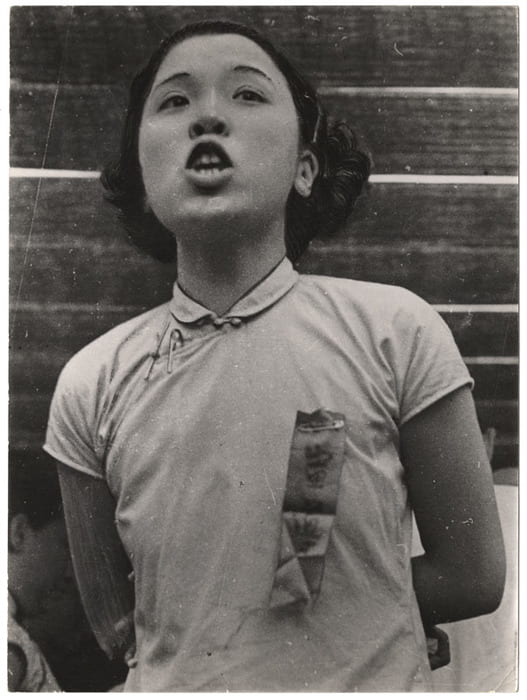

Dr Lucy Harris and two others having a wayside meal, on the way to Santai, Sichuan, c.1905. HPC ref: LH-s01.

As the photograph above might suggest, getting used to Sichuan food once chiles were super popular could take some adjustment! The variety of gazes is quite intriguing: the photographer gazing at traveling companions and at the local Sichuanese; the locals gazing at the foreigners; the child at the table gazing directly at the camera; one of the women at the table contemplating her meal (chiles?); her companion gazing at her reaction.

Fresh chiles, Kunming. Photograph by Brian Dott, 2017.

Initial use as a spice probably began as a substitute for more expensive flavourings, such as black pepper (imported), Sichuan peppercorn, and salt (government controlled). If the chile had remained merely a substitute, it would not have come to play such a key role in Chinese culture. Indeed, by the nineteenth century very few sources referenced its use as a substitute, instead emphasising it on its own merits. For this blog, I will introduce class roles in the spread of the chile and its role as a metaphor for revolution.

Dried chiles, Dunhuang. Photograph by Brian Dott, 2016.

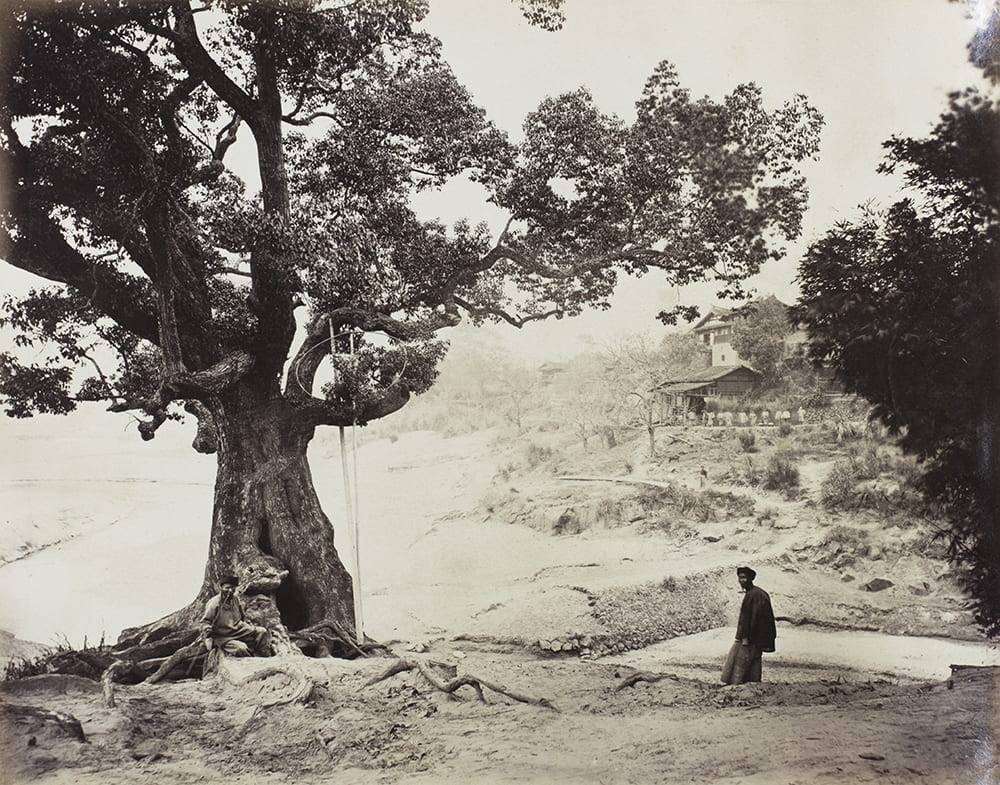

Modern sources about chiles in China tend to emphasise transmission and spread of chiles within China via merchants or traders. However, chiles did not become a widespread commercial crop until the late nineteenth or early twentieth century. Thus, the spread of chiles in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries actually happened in a different sphere. An important trait of the chile plant, which aided its spread around the globe, is that it can grow in temperate climates. Thus, unlike well-known spice trade spices, such as nutmeg, cinnamon, or cloves, which require tropical climates to grow, and therefore had to be continually imported to places with temperate climates, chiles could be grown in vegetable or kitchen gardens throughout most of China (gardens such as the ones shown below).

I argue that chiles spread within China primarily between neighbours. Seeds would have been passed from neighbour to neighbour, between relatives and communities that inter-married. The spread was at the grassroots level. The internal spread of chiles in China was markedly different from other American crops introduced around the same time. The sweet potato, maize, peanut and tobacco all received a great deal of written attention and promotion from both local and national elites. In contrast, no written sources prior to the twentieth century promoted the growing of chiles. With the history of the chile in China, reading between the lines of elite authored sources, we can see people taking their culinary and medical needs into their own hands.

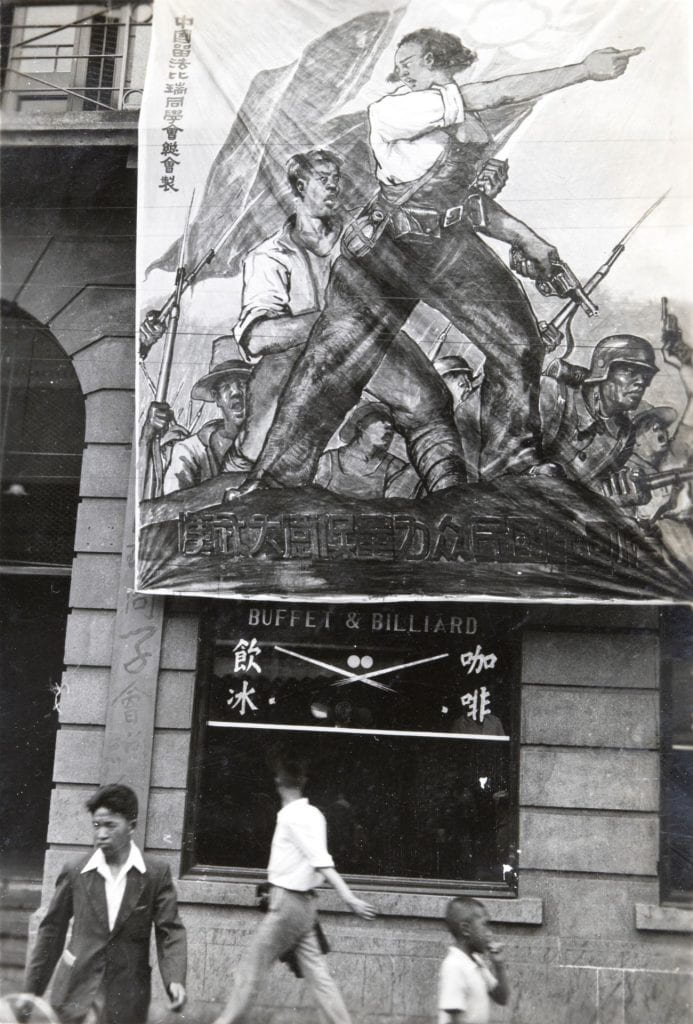

Beginning in the mid-twentieth century the Chinese began employing the chile as a symbol for military expertise and even for revolutionary success. Mao Zedong, a chile-loving Hunanese, absolutely adored eating chiles. He would tease people who ate with him if they couldn’t stand the heat. He even sprinkled chile flakes on his watermelon! At one point a doctor recommended that he cut back on his consumption of chiles, to which he acerbically quipped, ‘If you are even afraid of chiles in your bowl, how will you dare to attack your enemies!?’ Mao went even further in a conversation with American journalist Edgar Snow, asserting that the revolution would not be possible without the chile! Modern writers directly link the military prowess of Mao and other famous Hunanese military leaders with their chile eating.

Today a key component of Hunan regional identity is the ability to eat chiles. Mao is also an important symbol for Hunan, including his love for chiles. Many Hunan restaurants emphasise this connection with busts or portraits of the Chairman on prominent display. Menus often include dishes such as ‘Mao family red-braised pork.’ Below is the frontispiece from the menu of the Financial District Mao Family Hunan Restaurant in Beijing. Mao as revolutionary and chile-lover are both emphasised.