Drawing on a collection of photographs taken in Yunnan at the turn of the twentieth century, in this, the first of two blogs, Dr Andrew Hillier discusses what these images tell us about ‘the imperial gaze’ and the mind-set of a young Customs man in a remote treaty out-port.

PART 1- EXPLORING

A Remote Out-Port

The borderlands of Yunnan were as culturally remote from China’s coastal treaty port world as they were strategically sensitive during the last decades of the long nineteenth century. With British-occupied Burma (Myanmar) to the west and ‘French Laos’ comprising Annam and Tonkin, to the south, the Chinese authorities were keen to protect their borders from any further encroachment by the European powers. Britain and France, for their part, were equally keen to penetrate the ill-defined frontier and establish further spheres of influence and ‘the great highway to China’.[i]

As part of this strategy, the French established a treaty port at Szemao (also spelled Semao or Ssu-mao, now Simao), which lay close to the Laos border, and, in 1896, the British opened a consulate in the city, and the Qing a Maritime Customs station. However, the lack of other Europeans and any commercial prospects made it an unattractive posting. Sir Robert Hart, the Inspector-General, accepted that it was totally unsuitable for married staff in the Chinese Maritime Customs (CMC) and, after the British consul, G.J.L. Litton, had narrowly escaped being killed by local tribesmen, the consulate was closed and moved to the slightly less remote city of Tengyueh (Teng chong). [ii] It is, therefore, all the more surprising that Fred W. Carey (1874-1931), who was appointed to the Customs station when it opened, actually seems to have enjoyed the four years he spent there.

Fascinated by the landscape and the tribal people, Carey was an accomplished photographer and also an enthusiastic, if amateur, ethnographer. Supported by two articles, his images provide an exceptional record of the borderland area, lying to the south and south-west of the city, and the diverse peoples that lived there. [iii] However, given the imperial context, they also raise questions as to the purpose and effect of his activities, both as a photographer and as a collector of cultural artefacts.

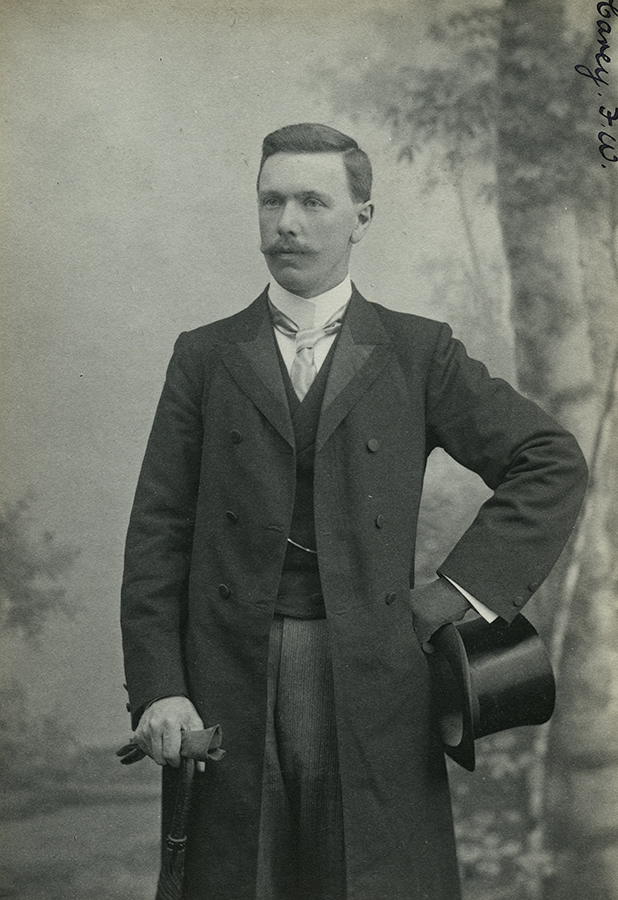

Having joined the CMC in 1891 at the age of nineteen, Carey had spent the first four years as a low-grade tide-waiter at Mengtze (Mengzi), another Yunnan border station where F.T. Carl was the Commissioner. Although a junior member of the (blue-collar) Outdoor Staff, he must have done well, because, when Carl was appointed Szemao’s first Commissioner, he was transferred to the Indoor Staff and appointed Fourth Assistant. This may also have been due to a family connection, because in a letter referring to the transfer, Hart noted, obliquely, ‘Curzon wrote about him’. [iv] Certainly, in this photograph, most probably taken in London, when he was on leave in 1902, Carey comes across as a suave young man. Puzzlingly, shortly before he took up his appointment, Carey was awarded Le Chevalier d’Ordre Imperial du Dragon d’Annam. Along with two Outdoor men, one European and one Chinese, this completed the Customs House staff.

A portrait of F.W. Carey by Maull and Co., a fashionable London firm, which had an arrangement with the RGS to photograph its members for the Society’s records. Presumably taken when Carey was on leave in 1902, it confirmed his standing as an amateur ethnographer of empire. © Royal Geographical Society (with IBG).

![The caption is problematic. In Carey’s writing, on the back of the photograph, it reads, omitting the phrase in brackets, ‘Group of [Chinese and] Customs officers at the official opening of the Semao Customs house’. On the front, written on the mount, presumably by the RGS, is the same caption but with the addition of the part in brackets. This would seem more accurate as, plainly, this is not the staff of the Customs house, save for Carl, in bowler, and Carey, in boater. In uniform on the left is the French Consul, Pierre-Rémi Bons d’Anty. The official in the centre may be the Daotai with other local officials and staff in the local bureaucracy. © Royal Geographical Society (with IBG).](https://visualisingchina.net/blog/files/2018/03/S0011536.jpg)

The caption is problematic. In Carey’s writing, on the back of the photograph, it reads, omitting the phrase in brackets, ‘Group of [Chinese and] Customs officers at the official opening of the Semao Customs house’. On the front, written on the mount, presumably by the RGS, is the same caption but with the addition of the part in brackets. This would seem more accurate as, plainly, this is not the staff of the Customs house, save for Carl, in bowler, and Carey, in boater. In uniform on the left is the French Consul, Pierre-Rémi Bons d’Anty. The official in the centre may be the Daotai with other local officials and staff in the local bureaucracy. © Royal Geographical Society (with IBG).

Custom House at Szemao; bales of cotton from the British Shan States sit outside. © Royal Geographical Society (with IBG).

Buffalo carts on a road in Szemao. There was also a striking contrast between Chinese architecture and that of the tribal people. Frederic Carey Collection, FC01-20 © 2011 Ann Kinross.

A Chinese temple. © Royal Geographical Society (with IBG).

A Shan house. © Royal Geographical Society (with IBG).

In Search of Tribal Culture

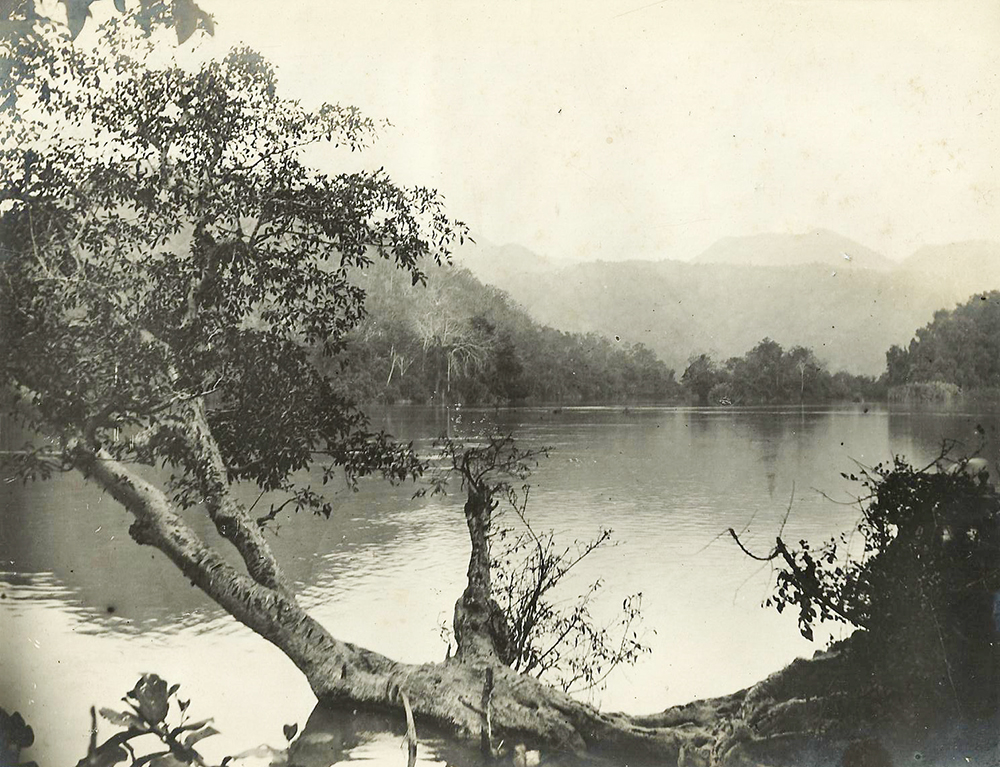

Carey soon decided that he wanted to explore these cultures. As he later told the (London) Camera Club, when he first arrived, he would obtain two or three days’ leave and ‘with a comrade visit the neighbouring hills in search of pictures…We would sleep out in the open, near water and pass the time shooting and exploring in very happy fashion’, a time that is captured in these images.

Bridge and Shen Lo (Water Pavilion), Szemao. Note the two Europeans on the bridge and how their distinctive clothing will have conveyed their ‘otherness’ to the local people. According to Carey, ‘all foreigners travelling in these regions are treated as officials’. Frederic Carey Collection, FC01-13 © 2011 Ann Kinross.

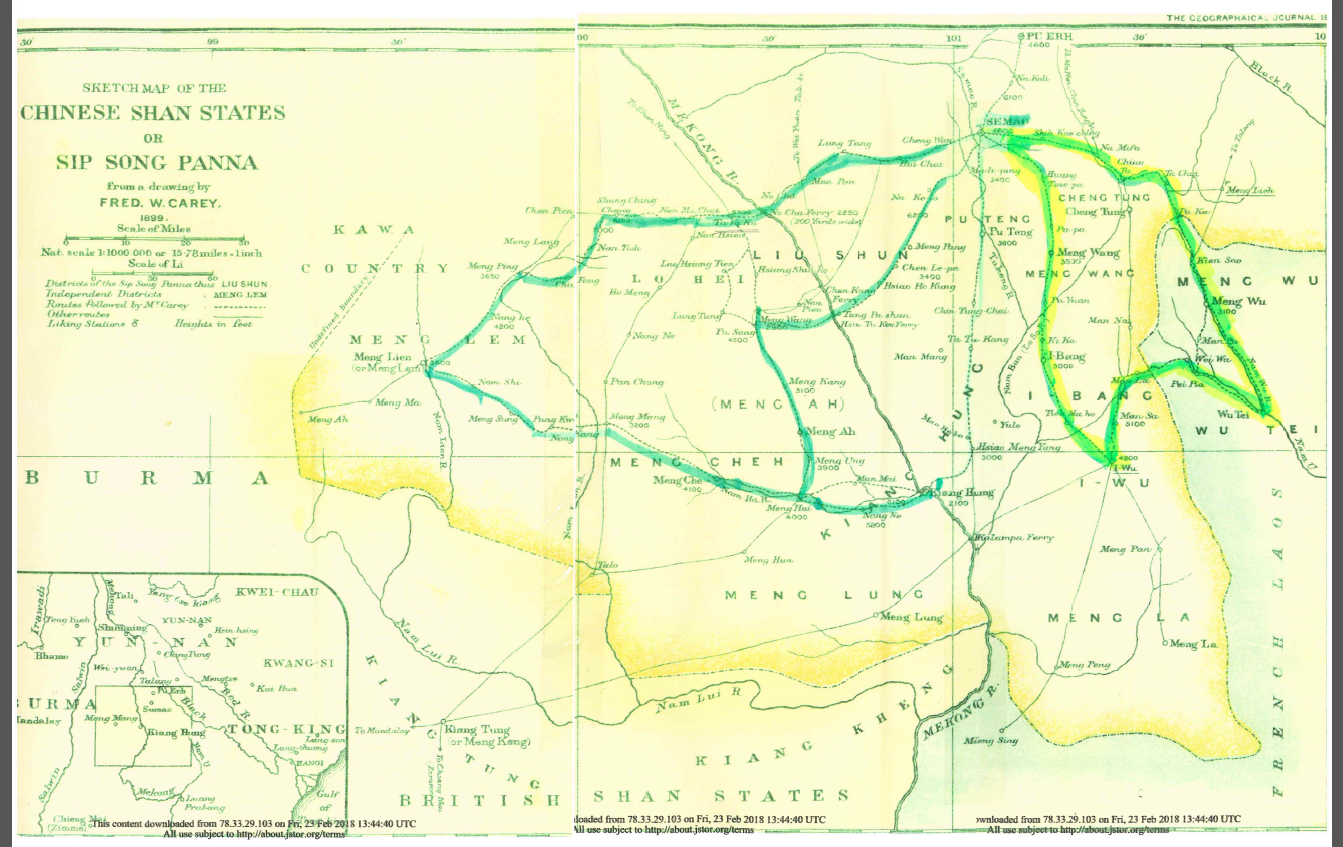

Soon this developed into a more serious interest, generated no doubt by the Darwinian quest for ‘primitive’ peoples and ‘the passion for collecting objects and artefacts’ that was a feature of the period. [vi] In December 1898, Carey made the first of two expeditions that would form the basis of the paper that was read to the Royal Geographical Society in February 1900, supported by lantern slides and a detailed map he had drawn. [vii]

Sketch map of the Chinese Shan States or Sip Song Panna, from a drawing by Fred. W. Carey, 1899 © Royal Geographical Society (with IBG).

In part, a travelogue and in part, an ethnographic study, the paper describes the complex ethnic identities of the various peoples that sprawled across southern Yunnan and into the adjoining countries: the Lolo (or Yi) and Kawa into Burma, and the Shan into the British Shan States (lower Burma) and French Laos, to the east of the Mekong river. Given the new imperialism that was sweeping across China, we have to ask how much this activity was designed to produce ‘knowledge about indigenous peoples and their social practices’ that could be deployed ‘to manage, monitor and re-organise [them]’, in the words of James Hevia. Moreover, by bringing these people within the ‘gaze’ of his camera, how much was Carey reinforcing a form of imperial appropriation, as some commentators would suggest? [viii]

Snapping

Whatever the answers, Carey’s enthusiasm was almost palpable, as he set off,

Though the muleteers raised hopes of an early start by putting in an appearance shortly after daybreak on the morning of December 4, 1898, there was, of course, the usual delay; for, after strapping all our belongings on to the saddle-frames, they disappeared, and we saw no more of them for several hours. To the inexperienced this kind of thing is trying; but good temper and patience are as indispensable to the traveller in Yunnan as an absence of nerves. These mental qualities, with some silver, a few tinned edibles, and a camp-bed, may be considered necessities; if, in addition, the traveller possesses a knowledge of the customs and language of the country, he is splendidly equipped.

As expected, the muleteers (‘mafus’) arrived and the caravan – Carey, his all-in-one servant/ ‘boy’/cook, together with a ‘coolie’ and a soldier – got started. Heading for the tea district of I-Bang, the purpose of the expedition seems to have been to identify the production levels of the various plantations and to map the likin stations, which collected the local goods- in-transit tax, which now formed part of the security for the Japanese Indemnity loan. Carey’s main interest, however, was in ‘snapping’ and classifying and, although the weather was initially poor, he was soon busy with his camera. As he explained in his RGS paper,

the Chinese regarded it with a good deal of suspicion, there being a widespread belief in Yunnan that foreigners have an instrument (chao pao ching) by means of which they are able to discover hidden treasures, and carry away the luck of a place in the shape of precious stones. But having seen the Likin Weiyuan go through the ordeal of having his portrait taken with equanimity, they were reassured …

However, this was not entirely frank, as he told the Camera Club,

the photos are in nearly every instance snapshots, taken without the knowledge of the victims. Indeed, had they guessed what I was doing … or the use I intended to make of them this evening, I should never have been able to obtain a single picture. [ix]

This does not mean that he was unwelcome. Invited to spend his third night in one of their houses, he ‘delighted’ the Lolo villagers when he played ‘some simple tunes’ on his banjo. ‘The young girls … started dancing outside the house, and though the only illumination came from my candle-lamp and some pine-wood torches, they kept it up until a late hour’. Free of any ‘immodesty’, the dancing was looked on as ‘a healthy amusement to be indulged in by both sexes’.

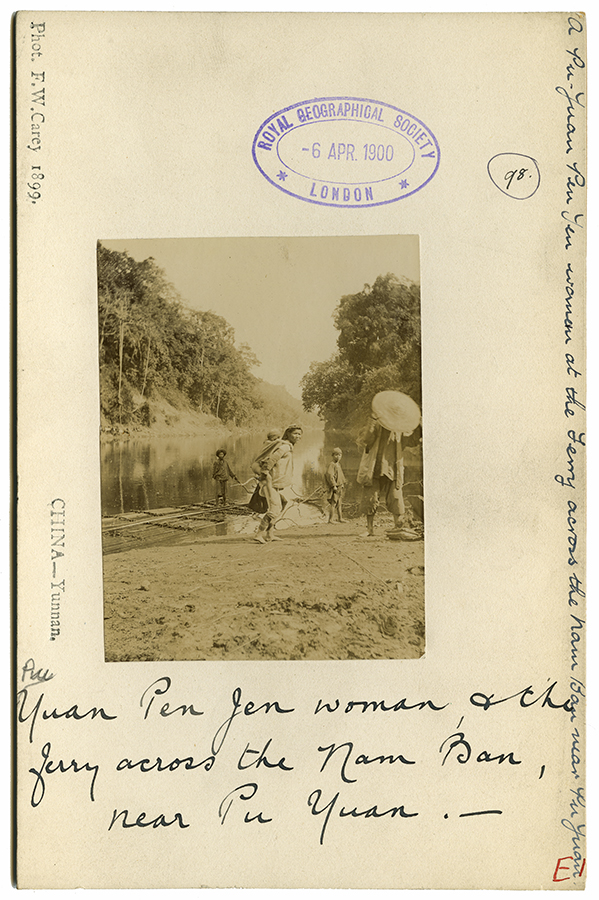

Carey was particularly interested in their clothing and, as he prepared to cross the Namban river, he managed to snap a woman from the Yuan Penjen tribe (whom he decided were part of the ‘Woni’ race). Their costume, he wrote

is very striking, consisting of a cloth hood, an open jacket, and a pair of short white trousers reaching barely to the knee. But the most important, though the least noticeable, part is their coloured cloth gaiters. These the women are obliged to wear, as without them it is believed they would be able to fly away, leaving their husbands and sweethearts sorrowful.

Yuan Penjen Woman. © Royal Geographical Society (with IBG).

Although ‘the idea was simply to obtain an illustration of the costumes’, the resulting photograph is overlaid with multiple meanings. Conscious of the ‘gaze’ of this western official, the woman was powerless to prevent her picture being taken (and it was an act of ‘taking’). Transposed from her familiar surroundings, she has been objectified and racialised as a ‘native’ in a remote and exotic landscape, with her clothing vested with superstitious beliefs. Used as an illustration for the RGS paper, captioned and archived, the image embodied an act of appropriation. [x]

Caravan of mules and ponies swimming a river. ‘… our luggage was piled up on a bamboo raft, on which we also crossed. The animals were urged by the muleteers into the water, and were made to swim across under a shower of stones and profanity.’ Frederic Carey Collection, FC01-29 © 2011 Ann Kinross.

Covering up to 25 miles each day, much of it uphill, and sometimes on foot, after just under five weeks, he returned to Szemao, arriving back on Christmas Day. He had travelled without any European companion and we do not know who, if anyone, was there to greet him on his return, with whom he celebrated Christmas and what sort of inner resources he had to sustain him in this remote out-post He seems to have been gregarious – at other ports, he took part in amateur theatricals and he would later marry and have four children. Yet here, there was almost no scope for any social relations, at least ones that complied with the conventions of the Customs Service. A question that applies to so many officials in the out-ports, it remains one of the enigmas of Britain’s intimate empire. [xi]

Returning with photographs, data and his findings, Carey had at least begun to formulate an understanding of the ethnic make-up. Whilst there were no more than five or six distinct ‘races’ in Yunnan, there were, he estimated, nearly a hundred differently-named ‘tribes’, which could be roughly categorised by location, customs, appearance and, to some extent, language. However, it was the knowledge that he had built up about their costumes that most interested Carey and this would be at the heart of his second expedition, when he set off three months later, as we will see in the next blog.

[i] Robert Bickers, The Scramble for China: Foreign Devils in the Qing Empire, 1832-1914 (London: Allen Lane, 2011), pp. 256-262.

[ii] Letter, Hart to Campbell, 22 March 1896 (1013), John K. Fairbank, Katherine Frost Bruner, Elizabeth Macleod Matheson (eds), The I.G. in Peking: Letters of Robert Hart, Chinese Maritime Customs, 1868-1907 (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1975), P. D. Coates, The China Consuls: British Consular Officers, 1843-1943 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988), pp. 316-318; a Sino-British agreement providing for trade with Burma was concluded on 4 February 1897.

[iii] At the same time as Carey was photographing this border area, James George Scott, the British Commissioner of the Burma-China Border Commission was making an extensive photographic record of the tribes to the west, including the Wild Wa (see British Library Manuscripts, Photos 92). There is no record of the two men ever meeting, although Carey does refer to the Commission in his RGS paper.

[iv] Letter, Hart to Campbell, (1026) 5 July 1896, Fairbank, The I.G. in Peking and see Catherine Ladds, Empire Careers: Working for the Chinese Customs Service, 1854-1949 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2013), p.131-137.

[v] The Chronicle and Directory for China, Japan etc for 1898 (Hong Kong: Hong Kong Daily Press, 1898), p.243. Many thanks to Robert Nield for this reference.

[vi] Amiria J.M. Henare, Museums, Anthropology and Imperial Exchange (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), p.210.

[vii] Fred. W. Carey, ‘Journeys in the Chinese Shan States’ The Geographical Journal (15) May, 1900), pp. 486-515. For the images at Historical Photographs of China, see https://www.hpcbristol.net/collections/carey-frederic and for the relevant section of the RGS on-line catalogue see https://rgs.koha-ptfs.co.uk/cgi-bin/koha/opac-search.pl?idx=kw&q=carey&offset=0&sort_by=pubdate_dsc 077043-077141. Twelve of the original 38 lantern slides survive (RGS 236232) Many thanks to Joy Wheeler, Information Officer (Photographs), RGS, for her assistance in relation to this blog.

[viii] James Hevia, English Lessons: The Pedagogy of Imperialism in Nineteenth-century China (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2003), pp. 20-21, E. Ann Kaplan, Looking for the Other: Feminism, Film and the Imperial Gaze (London: Routledge, 1997), pp. xvi-xvii, Eric Mueggler, ‘The Eyes of Others: Race, ‘Gaping’ and Companionship in the Scientific Exploration of South-West China’, in Denise M. Glover and Stevan Harrall (eds), Explorers and Scientists in China’s Borderlands (Washington: University of Washington Press, 2011), pp. 26-56 at pp. 52-53; for a discussion as to how much this sort of ethnographic exercise reflected an ‘Orientalist’ approach, see Margaret Byrne Swain, ‘Pére Vial and the Gni-p’a’, in Stevan Harrell (ed.) Cultural Encounters on China’s Ethnic Frontiers (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1995), pp. 140- 185.

[ix] With a Camera in Yunnan’, A Lecture delivered by Mr Fred W. Carey, FRGS, 2 April 1903, The Journal of the Camera Club (17) November, 1903, pp. 138-145 at p.141. For Chinese suspicion of Western photographers, see James R. Ryan, Picturing Empire: Photography and the Visualization of the British Empire (London: Reaktion Books ltd, 1997), pp.143-145.

[x] Cf. Mueggler, ‘The Eyes of Others’, p.53 and Mary Louise Pratt, Imperial eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation (2nd ed.) (London: Routledge, 2008), p.71; for the importance of photography to the RGS as an imperial institution, see Ryan, Picturing Empire, pp. 22-23.