Kaori Abe, who has written the post below, is a historian specialising in the history of Hong Kong and port cities in East Asia. The author of Chinese Middlemen in Hong Kong’s Colonial Economy, 1830-1890 (Routledge, 2017), she has worked in Singapore, the UK, and Switzerland and holds a PhD in History from the University of Bristol.

A decade ago, my grandmother, Abe Naoko (阿部 直子 née Futakami 二神), passed down to me her collection of old family photos of Shanghai and postcards of Hong Kong, which together make up the Abe Naoko Collection. What makes this collection unique is its portrayal of the lives of Japanese women within the Japanese community in the international settlement of Shanghai. In this post, I will explain the background and key photos from the collection, based on Naoko’s letter about her childhood life in Shanghai, my interviews with relatives, and consultation of primary and secondary sources.

Futakami Norizo (二神 範蔵) (1895–1972), my grandmother’s father, took the most of photographs in the collection. After graduating from a university in Japan, Norizo embarked on his career in Shanghai, working for Mitsui Bussan, a Japanese trading firm. He married Futakami Chitose (二神 千歳 née Oshima 大島) (1902–1987), who was a sister of his colleague, Oshima Kiyoshi (大島 清) at Mitsui Bussan in Shanghai in the late 1920s. Chitose left Japan to marry Norizo in Shanghai, and their wedding ceremony took place in there. Subsequently, the couple had two children while residing in Shanghai, with Naoko being their second daughter.

Fig. 1 Futakami Chitose and Oshima Shizuko(大島 静子) with a man, Jessfield Park (兆豐公園), Shanghai (上海) Abe, Naoko Collection KA-s29

The photograph above shows Chitose (left) and Oshima Shizuko (right), the man in the middle is thought to be one of Shizuko’s brothers.

In 1931, Norizo resigned from his position at Mitsui Bussan, taking responsibility for an embezzlement incident that occurred that year, and the family returned to Tokyo for approximately six months. While in Tokyo, they welcomed a third child into their family. Following Norizo’s acquisition of a new position at Yamashita Kisen (山下汽船), a Japanese shipping company, the family promptly returned to Shanghai, where they resided until 1934.

After the January 28 incident (also known as the Shanghai Incident) in 1932, when Japanese and Chinese troops fought a bloody month-long battle in the north of the city, the anti-Japanese movement intensified in Shanghai. In this context, between 1934 and 1935, the Japanese population in Shanghai decreased by nearly 3,000. The Futakami family was among those Japanese who left Shanghai and returned Japan as a result.[1] Upon returning to Japan, Norizo selected photographs taken during their time in Shanghai, creating separate albums for each of his children. The photographs featured in the Abe Naoko Collection come from the album handed to Naoko.

Fig. 2 Group of women and children in front a company house for employees of Mitsui & Co. (三井物産), Shanghai (上海) Abe Naoko Collection KA-s36

Photograph 2 shows a group of women and children standing in front of a company-owned house by Mitsui Bussan in Shanghai. This photo is likely to have been taken when the Futakami family lived in their first residence in Hongkou (虹口) district before Norizo resigned from Mitsui Bussan in 1931. In 1930, approximately 24,182 Japanese lived in Shanghai, most in the northern part of the international settlement, specifically the Hongkou district. Of them, 11,170 were women, making up 46.2% of Shanghai’s Japanese population. [2]

Fig. 3 Two women with three children standing on the pavement in front of a house in North Sichuan Road, Shanghai (上海) Abe Naoko Collection KA-s17

The third photograph above shows Futakami’s second residence in Hongkou district, featuring Chitose, three children, including Naoko, and their amah. According to Naoko, the family employed one or two amahs during their entire stay in Shanghai. The Futakami family was relatively well-off in the Japanese community. Still, the prevalence of diseases like cholera and typhus in Shanghai meant that “they lived with a certain degree of caution and preparedness,” as Naoko recalled.

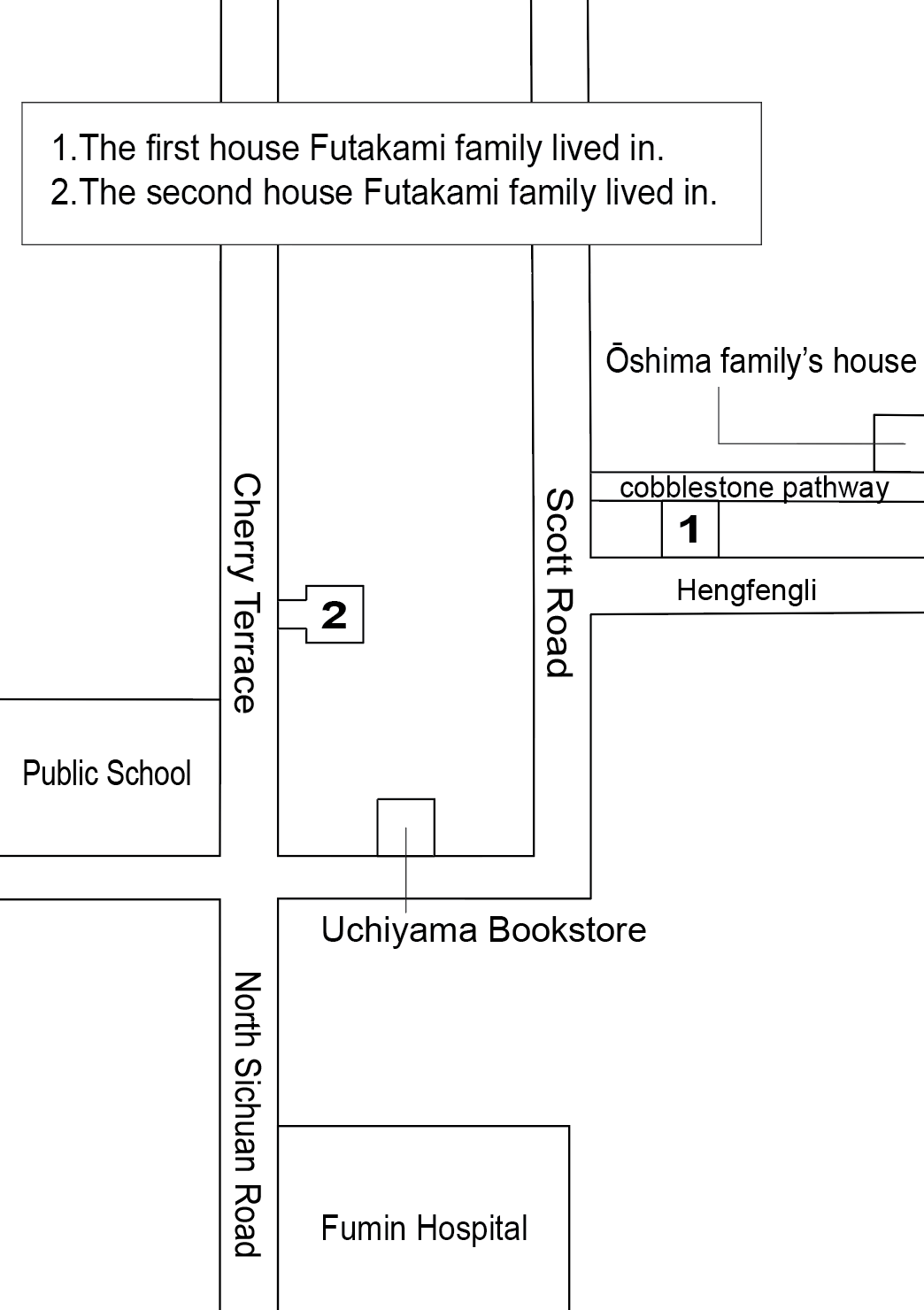

The Futakami’s first house was located at No. 4 Hengfengli (恒豊里), Scott Road (施高塔路, present-day Shannyin Lu 山陰路) and the second one was in Cherry Terrace (Qian’ai Li 千愛里 present Tianai Lu 甜愛路), North Sichuan Road (Beisihuan Lu 北四川路).

The first Google Map below indicates the location of Hongkou, while the second map illustrates the positions of Futakami’s first and second residences and their vicinity. I drew the second map by referencing a hand-drawn map and fragments of old Shanghai maps that Naoko and her family had crafted and gathered.

Fig. 5 Map showing the locations of the first and second houses of the Futakami family in Shanghai

The Uchiyama Bookstore (内山書店), a Japanese bookstore and a cultural exchange point between Chinese and Japanese intellectuals in Shanghai, was a few minutes’ walk from both of their residences. Influenced by her mother, a voracious reader, Futakami Chitose loved books and frequently visited the bookstore. Chitose seemed to often interacted with Japanese women who were also partners of expatriate Japanese, as evidenced by several photos of her and other women in kimonos at company events and gatherings.

The Japanese public school on North Sichuan Road was near Futakami’s second house.[3] Among the few English words Naoko learned in Shanghai were “public school”, “chauffeur,” and “wardrobe,” which her parents frequently used in their daily conversations.

Fig. 6 A photo of Hengfengli or Qiangai’li in Shanghia, 1985

Image 6 showing houses in Hengfengli or Qiangai’li was taken by a relative of Chitose, in 1985. When Chitose knew that her relative made a business trip to Shanghai, she asked him to find her former residence in Hongkou.

Fig. 7 Tianai Lu, Shanghai, 2012.

In 2012, my family, including Naoko, visited the same location. It was the first time my grandmother had revisited her childhood place in Shanghai. Photograph 7 is one I took when we found the Futakami family’s former residence in Qianai’li, now called Tianai Lu 甜愛路. “Tianai” literally meant “sweet love”. When we visited the street, many teenagers bought sweets from stalls and hung out there.

These are the context and supplementary explanations of the Abe Naoko Collection and my grandmother’s early childhood in Shanghai. Naoko married a person from Kobe, one of Japan’s former treaty ports, and his family was also deeply involved in business with China. My grandparents always enjoyed toast with jam and tea for breakfast. They regularly played tennis, and both were fluent in English. As I studied the history of Shanghai and the treaty ports in East Asia and delved into my family history, I understood why they embraced such a lifestyle. East Asian treaty ports incubated them, and they lived within that world.

Thanks to Helena Lopes, Jamie Carstairs and Robert Bickers for making this collection available at Historical Photographs of China.

[1] Fujita Hiroyuki藤田 拓之, “”kokusaitoshi” shanhai ni okeru nihonjin kyoryūmin no ichi: sokai gyōsei tono kankei wo chūshin ni”「国際都市」上海における日本人居留民の位置 : 租界行政との関係を中心に” (Japanese residents in the Shanghai international settlement), Ritsumeikan gengobunka kenkyū 立命館言語文化研究, 21 (4), 121-134, March 2010, p. 122.

[2] Dai go hyō 第五表 (table 5), Shina honbu narabi honkon, makao zairyū hōjin gaikokujin oyobi chūgokujin jinkō tōkei hyō 支那本部並香港、澳門在留本邦人外国人及中国人人口統計表 (The tables of Japanese and foreign population in China, Hong Kong, Macao), dai 23 kai第二十三回 (no. 23), Shōwa gonen junigatsu 昭和五年十二月(December 1930), A-15亜-15 (Gaimusho Gaikōshi Shiryōkan外務省外交史料館 Diplomatic Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan), Japan Center for Asian Historical Records (JACAR) <https://www.jacar.archives.go.jp/das/image/B02130022500>.

[3] The Shanghai Directory 1930: City Supplementary Edition to hte North China Hong List, Revised and Corrected to July, 1930 (Shanghai: North-China Daily News & Herald Limited, 1930), p.84.