Dr Helena F. S. Lopes is Lecturer in Modern Asian History at Cardiff University. She was previously a Leverhulme Early Career Research Fellow in History at the University of Bristol. Her book Neutrality and Collaboration in South China: Macau during the Second World War has recently been published by Cambridge University Press.

Nominally under Portuguese control since the sixteenth century until 1999, Macau has long been a territory shaped by regional and global connection and by the circulation of people, goods, and ideas. However, studies in the history of China’s foreign relations and European imperialism in China often ignore this small enclave. My book, Neutrality and Collaboration in South China, considers Macau in what were arguably the most dramatic years of its twentieth century history: 1937 to 1945. It reassesses the territory’s role in China’s War of Resistance against Japan, its links to neighbouring Hong Kong, and its importance to our understanding of neutrality in East Asia in the context of a global World War Two.

Nominally under Portuguese control since the sixteenth century until 1999, Macau has long been a territory shaped by regional and global connection and by the circulation of people, goods, and ideas. However, studies in the history of China’s foreign relations and European imperialism in China often ignore this small enclave. My book, Neutrality and Collaboration in South China, considers Macau in what were arguably the most dramatic years of its twentieth century history: 1937 to 1945. It reassesses the territory’s role in China’s War of Resistance against Japan, its links to neighbouring Hong Kong, and its importance to our understanding of neutrality in East Asia in the context of a global World War Two.

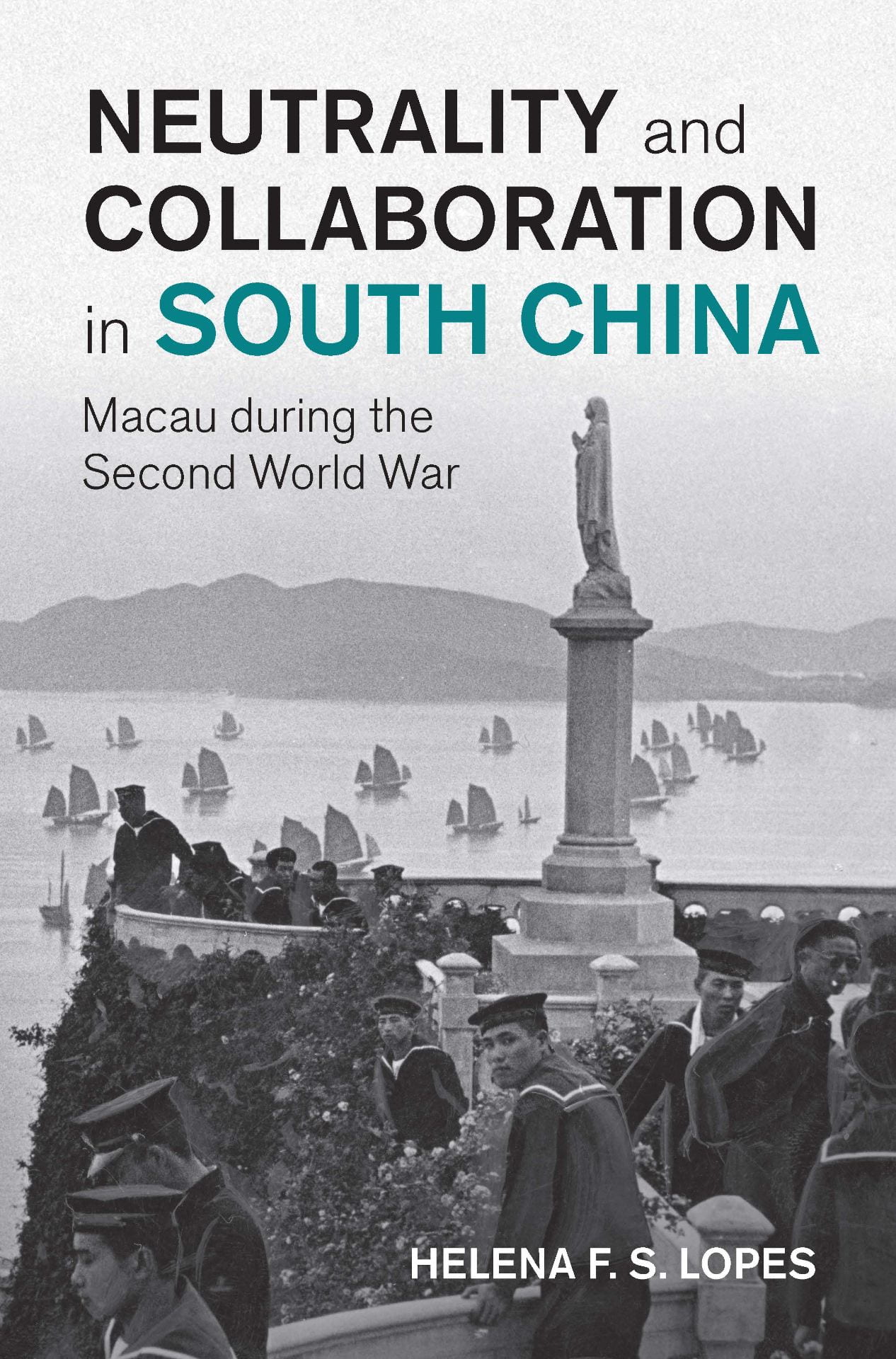

The photograph above showcases rather nicely the relevance of Macau’s maritime links. Although its land border with Guangdong province was also crucial during the war, many people reached the territory by boat during the conflict, and it was also by boat that several of them escaped, sometimes in hiding, to unoccupied China. Macau’s wartime experience had clear similarities to other territories under colonial rule in China that remained ‘neutral’ from 1937 until (at least) late 1941. This was the case of ‘lone island’ (孤島 gudao) Shanghai, Hong Kong and Guangzhouwan. Their foreign jurisdictions made them attractive havens for many refugees and resistance activists, and also popular bases for those engaged in collaboration with Japan. Macau belonged to this connected network of neutral territories in China and outlived them all, remaining the only one that was not occupied by Japan during the war.

2 Refugees fleeing Shanghai, The Bund, 1937. Malcolm Rosholt Collection. HPC ref: Ro-n0032 (this photograph is reproduced in Chapter 3 of the book)

In the book, I argue that Macau’s neutrality generated overlapping layers of collaboration involving a range of actors with different interests, including Chinese Nationalists, Communists and collaborators with Japan, British and Japanese representatives, Portuguese colonial authorities and refugees of different nationalities. I highlight the importance of refugees as central to Macau’s experience during the war and consider the post-war implications of wartime neutrality.

Amongst those connected to Chinese resistance activities in Macau were some very important Nationalist figures, including Wu Tiecheng (on the left in Fig 3, below) who led Kuomintang activities in Hong Kong and Macau in the late 1930s. The family of diplomat Fu Bingchang (standing next to Wu in the photo) also stayed temporarily in Macau during the war.

The book also zooms in on the activities of Chinese diplomats in Portugal, providing a fresh look into the vitality of China’s wartime diplomacy by analysing relations with a small European power. Macau was a cosmopolitan place during the war and so was Lisbon, the distant capital where the territory was often a topic of discussion between Chinese diplomats and Portuguese officials. Both were sites of meetings, refuge, and gateways to somewhere else. Amongst those who passed through the Portuguese capital was the eminent Chinese diplomat Wellington Koo (Gu Weijun) – who served as ambassador in Paris and London during the war – and his wife Oei Hui-lan (Huang Huilan: Fig 4), the latter having sought temporary refuge in Portugal after fleeing occupied France.

4 Madame Wellington Koo (née Hui-lan Oei), 1943

Photograph by Bassano Ltd © National Portrait Gallery, London

Turning from international connections to events closer to Macau’s borders, the book also delves into the Portuguese failed attempts to occupy islands near the territory, including the one known then as Lappa (now part of Zhuhai). The Chinese Maritime Customs station at Lappa featured in some of the dramatic events. Historical Photographs of China holds several rare images of the Lappa Customs station in the early twentieth-century, such as the one below (Fig 5).

5 The Assistants’ House, Lappa Customs Station, Lappa Island, c. 1906-1909. Reginald Hedgeland Collection. HPC ref: He01-207

Thousands of Hongkongers moved to Macau during the war where they were involved in a range of activities, including in planning for a British return to Hong Kong (shown below in 1945). Exploring in detail the experience of Hong Kong refugees in Macau and the role of the British consulate headed by John Pownall Reeves, the book sheds light on overlooked features of Allied resistance in South China during the Japanese occupation of the British colony.

Despite their differences, Macau and Hong Kong were deeply connected and those connections were embodied in the many people who moved between the two territories. Their post-war journeys would continue to have important, albeit understated, links. This is something I shall be exploring further in my next project.