Our latest post comes from Xavier Ortells-Nicolau, an adjunct professor at the Department of Modern Languages and Literatures and English Studies, Universitat de Barcelona. His recent work has focused on images of China in late nineteenth and early twentieth century Spanish media and on the figure of Juan Mencarini, a Customs employee and amateur photographer who promoted photography associations in Shanghai and Fuzhou.

The seal of the Municipal Council of the International Settlement in Shanghai famously included the flags of the some of the foreign states that composed that multinational enclave: the United Kingdom, the United States, and Japan — those with the largest number of residents and greatest economic power — but it also contained the emblems of smaller European countries such as Denmark or Spain, with a minor role in the history of the treaty ports. The presence of Spaniards in the treaty ports increased after the loss of the Philippine colony in 1898 and in the 1920s and 1930s one might find a hat store named La Espana or a Sevilla restaurant in the French Concession.[1] Among the foreign communities of Fuzhou, Hankow or Xiamen one would surely meet Spanish diplomats and businessmen, and venturing into the interior (as china beyond its maritime or riverine territories was once routinely known), any of the countless Spanish Catholic missionaries, distributed along vicariates and provinces: Augustinians in north Hunan, Franciscans in Shaanxi, Dominicans in Fujian, and Jesuits in Jiangsu and Anhui.

Advertisement for the Sevilla Restaurant published in Le Journal de Shanghai, 29 June 1935. Located in Avenue du Roi Albert (Shaanxi Nanlu), the restaurant was opposite the Shanghai Hai-alai Auditorium, where the Basque pelotaris who opened the restaurant in 1930 played. Source: Archivo China-España.

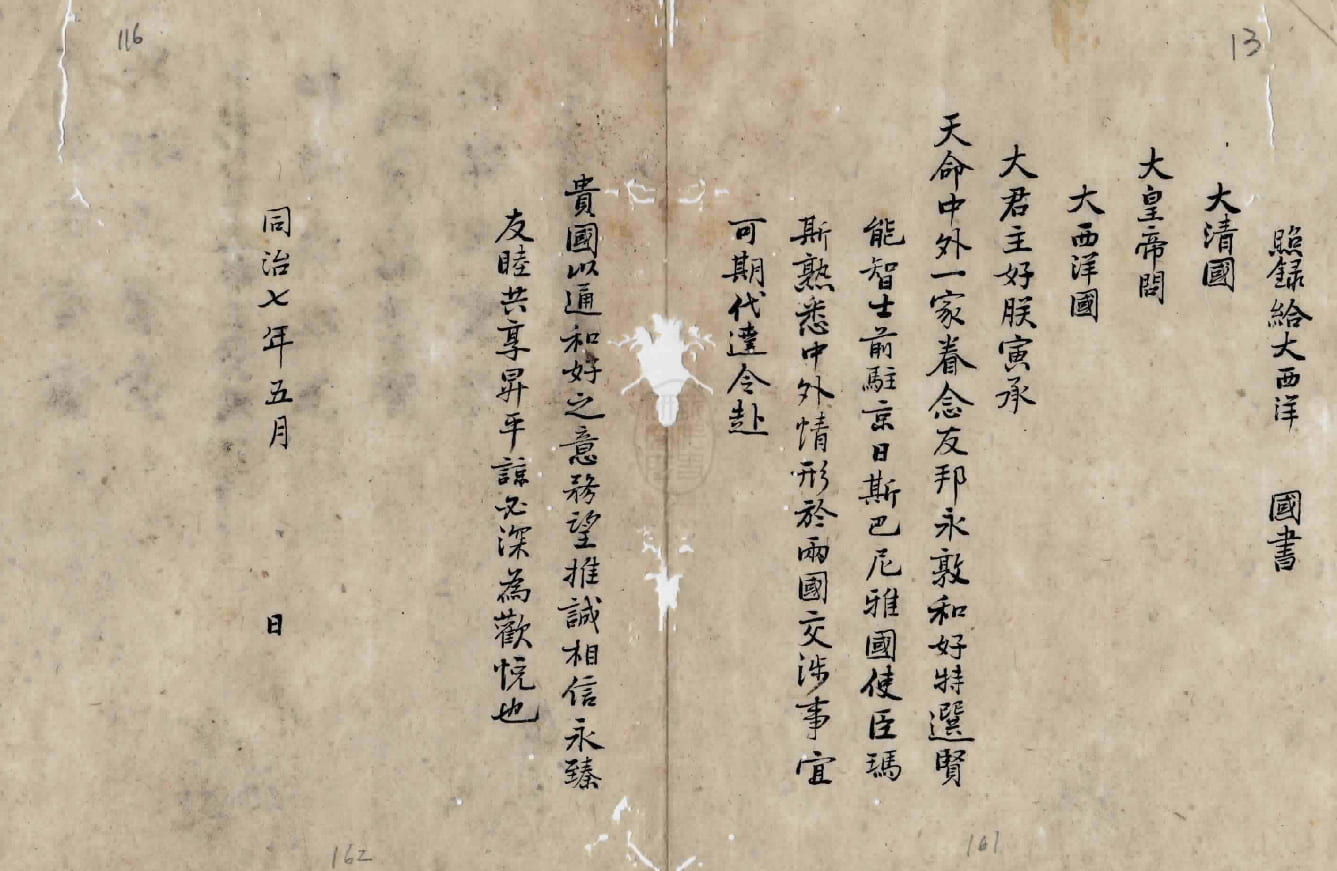

Over the last decades, different research projects have been looking into the activities and presence of the nationals of Norway, Italy, the Netherlands or Hungary in nineteenth and early twentieth century China. ALTER at UOC-Barcelona, a research group led by Carles Prado-Fonts and David Martínez-Robles and focusing on the Sino-Spanish relationships, has produced outcomes that reveal a limited but nonetheless significant impact: the first Sino-Spanish treaty in 1864, for example, was a much less unequal business than other treaties, as it granted the most-favoured-nation clause … to China; its negotiation depended on the skills of Sinibald de Mas, who was later required by the Zongli Yamen to act as secret agent in an operation to get Macao back.[2] In a recent publication, Monica Ginés-Blasi has dissected the schemes of Spanish merchant-consuls in the coolie trade off Xiamen.[3] These and many others cases exemplify the contributions that such from a peripheral perspectives can afford to the historiography of the Western presence in China’s ports, and the extent to which cases like the Spanish one can provide some nuance to our understanding of the ‘Western’ presence in China.

Many of the images in this blog entry come from yet another outcome of ALTER’s research, the Archivo China-España, an online catalogue of images, documents and pieces of historical media covering Sino-Spanish relationships during the 19th and 20th centuries up to Franco’s regime. In addition to individual entries, the archive (for the moment, mostly in Spanish) includes narrative itineraries and visual collections, such as the one obtained by Diplomat Enrique Otal y Ric in China. In a photograph included in the collection, four bearers and other attendants, ready to carry a sedan chair, pose in front of a building credited as the residence of the Spanish minister in Beijing between 1876 and 1879, Carlos Antonio de España. Behind a white pony, three Western figures are discernible, including Minister de España next to a pillar (with a beard) and Otal y Ric to his right wearing a bowler hat.

Mandarin’s Chair. Source: Archivo de los Barones de Valdeolivos de Fonz, Documentos y Archivos de Aragón, Gobierno de Aragón, Enrique Otal y Ric Collection. Archivo China-España.

Research into Historical Photographs of China’s virtual archive has opened a fascinating line of inquiry into the circulation of China images in the nineteenth century. In the National Archives in Kew collection, we can see a second print of the same negative, which credits the photograph to Thomas Child. However, in this copy the three Spanish diplomats have disappeared: actually, traces of the erasure are evident as spectral presences over the window.

This photograph is in an album in The National Archives, London, entitled ‘The Chinese Customs in Peking 1889-1891’ (CO1069-421). The photograph is signed by Thomas Child and captioned in the album: Mandarin Chair. HPC ref: NA01-90.

Later on, the same photograph would be reproduced as a postcard by Max Nössler in Shanghai, and in turn confirmed it as an image of a “chair of a mandarin”, in addition to favouring the relocation at convenience, as in this postcard send from Shanghai to Würzburg in 1901.[4] As if it were true that a picture is worth a thousand words, the vicissitudes of this negative stand for the historical irrelevance of Spanish presences in China, which ALTER’s research has worked to correct.

A post card published by Max Nössler & Co., 38 Nanking Road, Shanghai, c.1907, entitled ‘Mandarins chair’. Source: Archivo China-España.

As Carles Prado-Fonts[5] has amply demonstrated, the mediations of English and French cultures were key in the China-related knowledge and literature of fin-de-siècle Spain. That is why the few cases of Spaniards with direct knowledge of China in the nineteenth and early twentieth century become particularly relevant. A case in point is Juan Mencarini, a middle-ranked Imperial Maritime Customs Service employee, esteemed philatelist and photography aficionado with a key role in the development of photography in China. I have explored at large Mencarini’s life, career and photographs in the paper ‘Juan Mencarini and Amateur Photography in Fin-de-siècle China’.

Mencarini standing in the foreground at the summer resort of Gustav Siemssen (who is sitting to the left of Mencarini at the front, wearing a dark waistcoat and a cap). HPC ref: Os03-075.

In 1891, Mencarini was deployed to Fuzhou to act as Second Assistant B under the Hungarian commissioner Edmund Faragó. It was not long after his arrival that, as he had just done during his previous service in Shanghai, he joined other foreigners (like Siemssen) in creating the first club of amateur photographers in town, the Foochow Camera Club. In 1893, the club organized an exhibition of photographs of its members. A review published abroad described Mencarini’s works: it commended high praise ‘to No. 18, ‘Foochow Autumn Races, 1892’, taken at the time of presentation of ‘The Ladies’ Purse’. Full of figures, each one comes out in the picture with singular clearness, and the faces of each are easily recognizable’, [6] a description of a scene which is recurrent in HPC.

If not for the blurred figures, this might be Mencarini’s photograph at the Fuzhou races of December 1892. From the John Oswald collection, HPC ref: Os03-074.

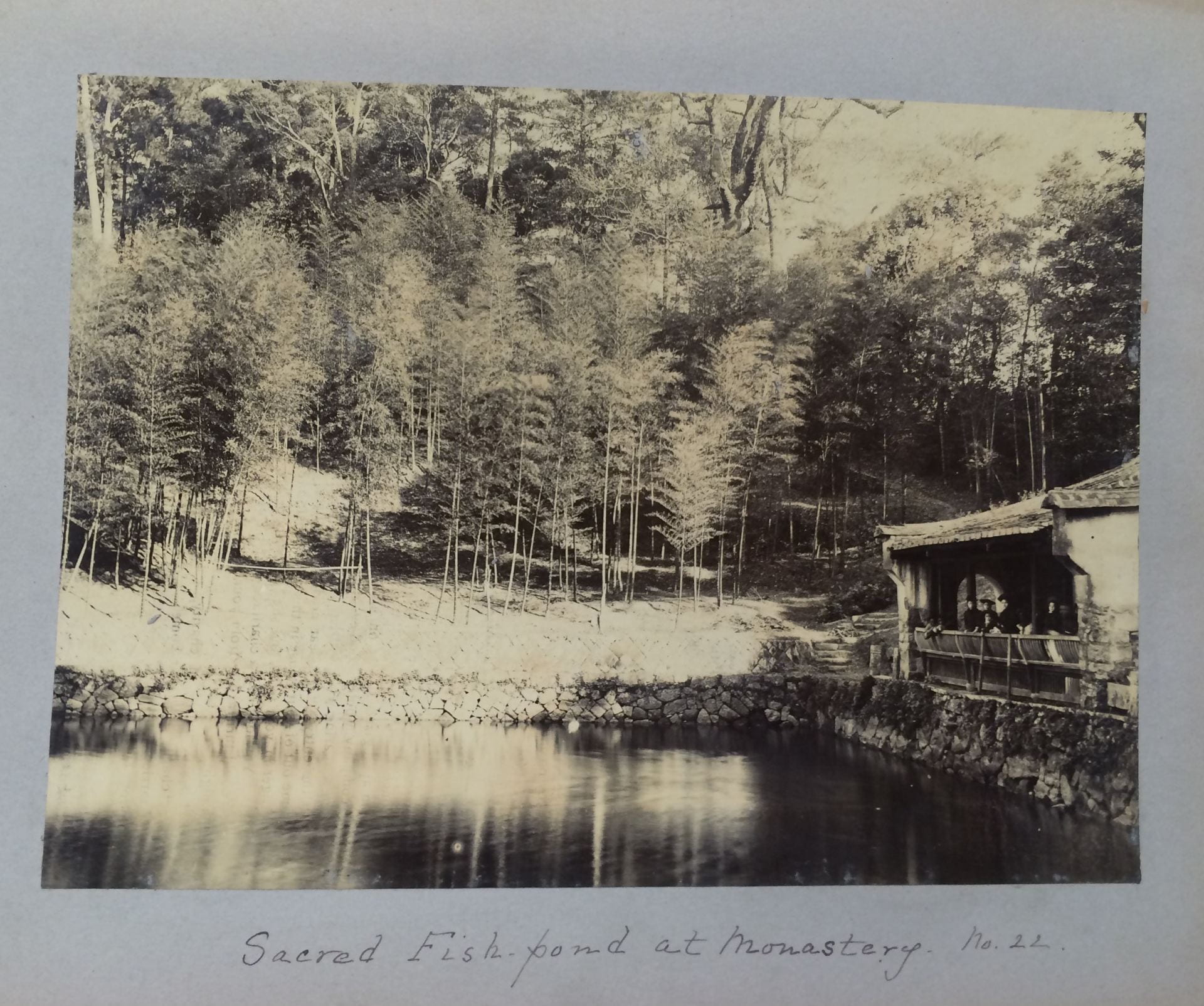

Similarly, the review noted that his photograph of the ‘Sacred Fish Pond’ at Gushan Monastery was ‘distinctly good’. This photograph, reproduced in different albums and press articles, is easily identifiable among Mencarini’s preserved works. In it, Mencarini tried to capture the reflection on the water of the trees in the background, while drawing our attention to a number of female figures standing at the veranda of the right hand pavilion, located at the entrance of the Buddhist mountain compound of Gushan, then on the outskirts of Fuzhou. In words of the North China Herald when the image was exhibited in Shanghai, the photograph has “all the charm of picturesqueness with the added touch of life in a few figures”.[7]

Juan Mencarini, “Sacred Fish Pond at Monastery. No. 22”, Foochow Album, Harvard Yenching-Library. Reproduced with permission in Archivo China-España.

This image presents us with another felicitous case of visual collaboration across repositories, as an image attributed to the local studio Tung Hing shows the spot from where Mencarini obtained his image. As if granted a peek behind the scenes, we can perhaps imagine the moment of the shot, with the photographer standing on the stones that line the road and directing the people posing in the pavilion.

Fishpond and paved approach to Buddhist monastery of Kushan, near Fuzhou. Photograph attributed to Tung Hing. HPC ref: Hv36-43.

The provincial capital Fuzhou, its famed tea district in the Wuyi Mountains north of the province of Fujian, and its variated river courses provided some of the most reproduced landscapes and vistas of the last quarter of the nineteenth century in China. Even though by the time Mencarini arrived to Fuzhou the tea trade was in decline, he was similarly attracted, like professionals and amateurs alike before him, to the picturesqueness of the sumptuary or religious constructions, like the horse-shoe tomb of the revered local official Chen Ruolin and the Gushan and Yuanfu monasteries. Albums by him or including his images, owned by friends or colleagues at the Customs, featured agricultural scenes, the lush riverbanks of the Min River, or the Jinshan temple on an island.

Quite idiosyncratically, Mencarini was as attracted to the aesthetics of photography as to their pedagogical power. He used them in press articles and magic lantern projections to elaborate historical and economic narratives of the different regions he got to know during his service in the Imperial Customs (as was also member of the Royal Asiatic Society). A North China Herald report on a lecture in April 1905 offers us a glimpse of Mencarini’s style:

Mr. Mencarini has done a great deal of camera work in this beautiful country and it will be remembered that he won the gold medal at the recent exhibition with a picture taken a few miles from Foochow. He was able to illustrate his remarks last night with some excellent views of scenery which he did not hesitate to compare with that of Switzerland and the Riviera. Mr. Mencarini supplemented his purely descriptive passages with a sketch of the history of the port, from the time of the first Portuguese traders in the 16th century through the period of its 19th century prosperity, till the present time, when “through the unpardonable neglect of the natives”, the tea trade has departed to India. A similar fate may overtake another leading industry, Mr. Mencarini said, unless speedy steps are taken to check the wholesale felling of the pine forests, the lumber of which is a considerable export.

A Foochow pole junk, with a full cargo of poles, Shanghai. Photograph by Charles Ewart Darwent. HPC ref: Da01-21.

[1] http://ace.uoc.edu/items/show/649

[2] See David Martínez-Robles, ‘Constructing sovereignty in Nineteenth century China: the negotiation of reciprocity in the Sino-Spanish Treaty of 1864’. International History Review, 38: 4; Entre dos imperios Sinibaldo de Mas y la empresa colonial en China (1844-1868), Marcial Pons, 2018.

[3] Mònica Ginés-Blasi, ‘Exploiting Chinese Labour Emigration in Treaty Ports: The Role of Spanish Consulates in the “Coolie Trade’, International Review of Social History, 1-24.

[4] http://project-postcard.com/november-1901-a-mandarins-chair-with-carriers-in-shanghai

[5] ‘Disconnecting the Other: Translating China in Spain, Indirectly’, Modernism/Modernity, 3. 3, 2018; ‘Writing China from the Rest of the West: Travels and Transculturation in 1920s Spain‘. Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies, Vol. 19: 2, 2018.

[6] Anthony’s photographic bulletin, vol. XXIV, no.11, 10-6-1983.

[7] The North China Herald, 24 February 1905.