Dr. Helena F. S. Lopes is a Leverhulme Early Career Research Fellow at the Department of History, University of Bristol. This posting is part one of three-part series on the ruins of Macau.

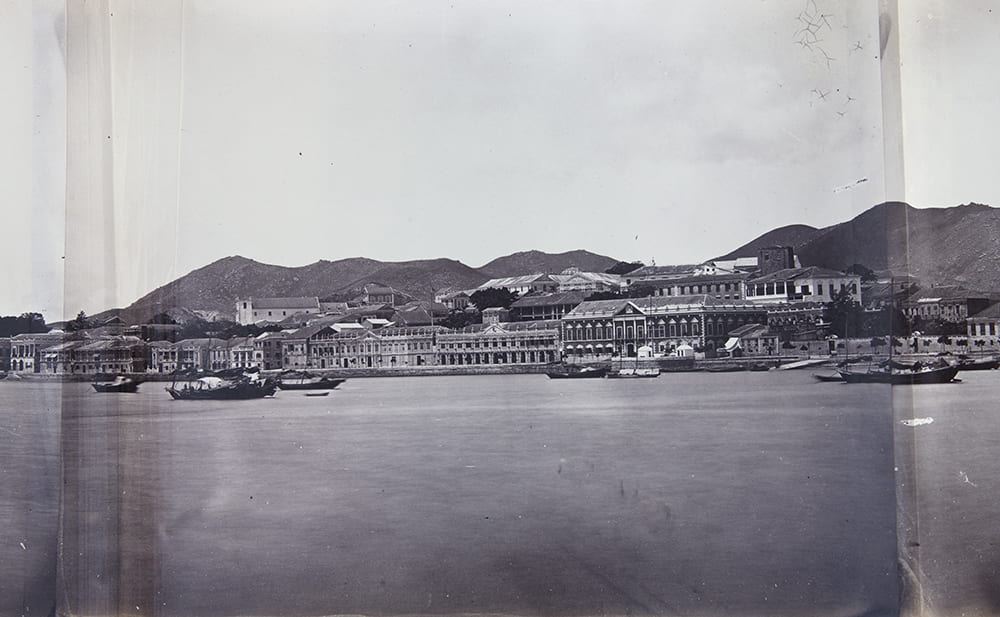

Part two of a panoramic view of the Praia Grande (南灣), Macau, c.1868. Photograph by William Pryor Floyd. HPC ref: VH03-61.

The South China territory of Macau (澳門) was the first European settlement in the country, with the Portuguese presence there dating back to the 16th century. It returned to Chinese rule in 1999, two years after Hong Kong. Historical Photographs of China holds a small but interesting sample of images of Macau in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The images currently on the website stop in the early 1900s, but a small collection of commercially produced 35mm slides (entitled on the box ‘20 Colour Slides Of Macau Scenery’ and in Japanese ‘20枚スライドにマカオの名勝’) in the Colin and Janet Andrew Collection held at the University of Bristol Special Collections (DM2818/3) offers other views of ‘old Macau’. Amongst these slides, which date from the 1970s, we find some popular old landmarks, often featured in depictions of the city (e.g. Ruins of St Paul, A-Ma Temple) alongside what were, then, relatively new places (like the Hotel Lisboa, built in 1970, or the Governador Nobre de Carvalho Bridge/Macau-Taipa Bridge, opened in 1974). Interestingly – some of the sites promoted in the slides have since ceased to operate, becoming a kind of ruin, too.

The Praia Grande shown in the photograph above is part of a four-part 1868 panorama by William Pryor Floyd, an early China photographer who had his studio there before moving to Hong Kong. The bay has changed so much in the last one hundred years due to land reclamation and rebuilding that those views from the water, a common topic of turn-of-the-century postcards of Macau, are themselves images of something largely gone. As other places around the world, Macau has its share of ‘ruins of empire’ which invite meaningful discussions on the material and immaterial legacies of colonialism. Ruins are remains, they are physically present, but that semi-destructed state also evokes what has since vanished. Ackbar Abbas’ discussion of a ‘culture of disappearance’ in Hong Kong is also fruitful to understand its connected neighbour.[1]

When speaking of Macau, it is not uncommon that one’s immediate visual reference is the Ruins of St Paul, most notably the stone façade that remains of the Church of the Mater Dei (Igreja da Madre de Deus) and St Paul’s College (Colégio de São Paulo), built by the Jesuits in the 16th century and rebuilt in the early 17th century. The buildings were almost completely destroyed in 1835, due to a fire but the sculpted façade survived. The impact of natural disasters and man-made destruction has always had a more pronounced role in reshaping Macau’s landscape than military conflict.

Now recognised as a UNESCO World Heritage Site as part of the ‘Historic Centre of Macau’, the Ruins of St Paul can be found in some of the HPC photographs. The image above, dated ‘May 22 & 23 1911’, some months before the Chinese Republican revolution, is from an album that belonged to a member of ‘Pelissier’s Follies’, a British theatre troupe who toured East Asia in 1911.

It bears some similarities with a photograph taken by Scottish photographer John Thomson in 1870. The almost deserted staircase towered by the imposing façade is flanked by old buildings on one side. A solitary figure approaches the foreground, with no distinguished features, a silhouette in a land of shadows and light. The contrast couldn’t be sharper with the crowds one would have encountered if visiting the site by day in the pre-Covid-19 tourist boom days.

The ruins of St Paul are a fitting symbol of several dynamics one can associate with the territory. For a start, there is of course the Catholic presence in China, in whose rich history Macau holds a very important place. There is the much-cited coexistence of different communities and influences, even beyond the obvious Chinese and Portuguese – for example, the façade was carved by Japanese Christian refugees working under the direction of an Italian Jesuit priest. It is also testament to the history of the foreign military presence in China, as the college (which had ceased to operate when the Society of Jesus was expelled from the Portuguese empire in 1762) was later used as military barracks, the 1835 fire having started in its kitchen. Its present incomplete and hollow form can invite discussions on the exercise and legacy of Portuguese colonial power in Macau. Its restoration and marketisation as a tourist hotspot also tell a story of rebranding, commercialisation, and development in the running up to and since the 1999 handover. Little wonder, then, that the place has attracted considerable scholarly attention.[2]

St Anthony’s Church, damaged by the 1874 typhoon, Macau. Photograph by Lai Fong (Afong Studio). HPC ref: NA15-18.

Amongst the HPC holdings one finds another photograph of the ruins of a church with Jesuit connections: an impressive photograph by Lai Afong Studio of St Anthony’s Church (Igreja de Santo António) in the aftermath of the 22 September 1874 typhoon. The photograph comes from an album in the UK National Archives documenting typhoon damage in Hong Kong and Macau. St Anthony’s Church is one of Macau’s oldest churches, first built using bamboo and wood in the mid-sixteenth century, and later rebuilt in stone. It too suffered its share of destruction by fire but it still exists, its present building dating from the 1930s. Its successive rebuilding says something about the endurance of Macau’s Christian communities.

These photographs of religious ruins offer a glimpse of past versions of monuments that are still standing. But other, more recent, images in the HPC collection have arguably more obvious links to ideas of disappearance and legacies of empire, as we shall see in the second of this three-part series on ‘Ruins of Macau’.

Ruins of St Paul’s Cathedral, Macau, c. 1975. HPC ref: Aw-t526.

[1] Ackbar Abbas, ‘Building on Disappearance: Hong Kong Architecture and the City’, Public Culture 6 (1994), pp. 441-459.

[2] E.g. Cristina Mui Bing Cheng, Macau: A Cultural Janus (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1999), pp. 83-100; Cathryn H. Clayton, Sovereignty at the Edge: Macau & the Question of Chineseness (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009), pp. 1-5 and passim; Gonçalo Couceiro, A Igreja de São Paulo de Macau [Macau’s St Paul’s Church] (Lisbon: Livros Horizonte, 1997); Lee Yuk Tin, Olhar as Ruínas: Igreja da Madre de Deus em Macau [A View of the Ruins: The Mater Dei Church in Macau] (Macau: Livros do Oriente, 1990); Marta Wieczorek, ‘Macau’s Heterotopias: Ruins of St Paul’s as a Spatial and Temporal Disruption’, The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology 20/4 (2019), pp. 312-327.