Jamie Carstairs, who manages the Historical Photographs of China Project, follows up serendipitous events, leading to a rabbit hole, in which a ‘new’ nineteenth century China photographer was found.

‘Mr. C. F. Moore, in the service of the Customs at Ningpo, has been staying here in the same temple with us. He seems an enthusiastic photographer, and spends most of his time in taking views of the surrounding country. He has a sedan chair ingeniously contrived for his operations, which his coolies (sic) carry about the country wherever he goes. I hope to induce him to spare me a few views.’ So wrote Thomas Hanbury in a letter to his father when staying at the “Temple of Shih Douzar, about 40 miles from Ningpo” in October 1870. [1]

Following on from this intriguing snippet, I started working with the Royal BC Museum in Canada, identifying buildings and locations depicted in ninety-nine glass plate negatives by Charles Frederick Moore (Royal BC Museum ref: MS-3171) that they hold. I was pleasantly surprised to see among them, three negatives which brought to mind prints made from them, being photographs taken in Zhapu (Chapu), a coastal town half way between Shanghai and Hangzhou. These prints are in an album in the Edward Bowra Collection: Bo01-044 (below) is off the negative with the Royal BC Museum reference J-00445. Bo01-045 is from negative J-00452. Bo01-046 is from J-00458.

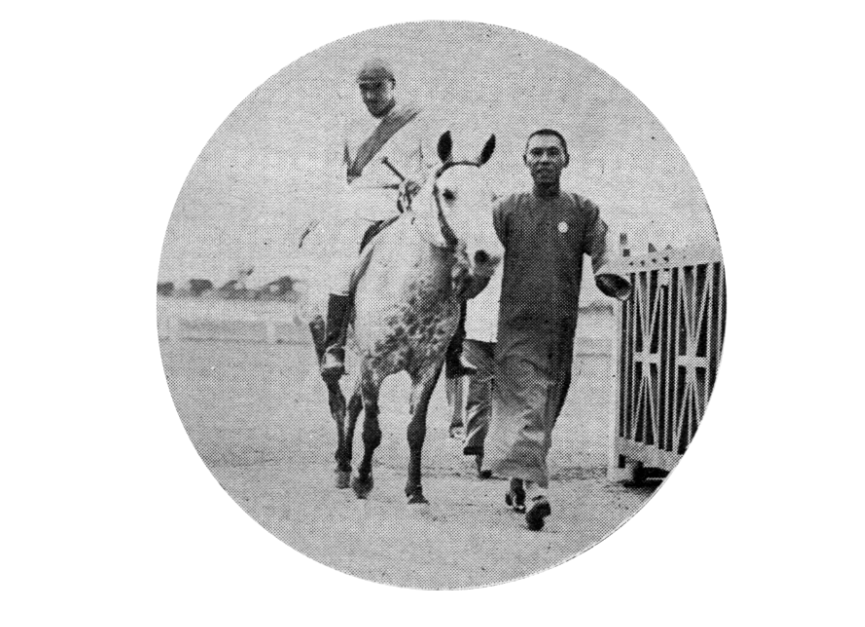

Fort Chapu, Zhapu, north Zhejiang, c.1870. Photograph by Charles Frederick Moore. HPC ref: Bo01-044.

Another Moore negative (Royal BC Museum ref: J-00444) is of a pagoda at the Changchun yuan (长春园; 長春園), the Garden of Everlasting Spring, at the Yuanming Yuan, the Old Summer Palace, Beijing – discussed and reproduced in Nick Pearce’s Photographs of Peking, China 1861-1908 (Edward Mellon Press, 2005), plate 31 and page 119. This rarely photographed and distinctive pagoda with a round top, stood until 1900. The photograph can be considered to be by C.F. Moore, rather than ‘possibly’ by Dr John Dudgeon.

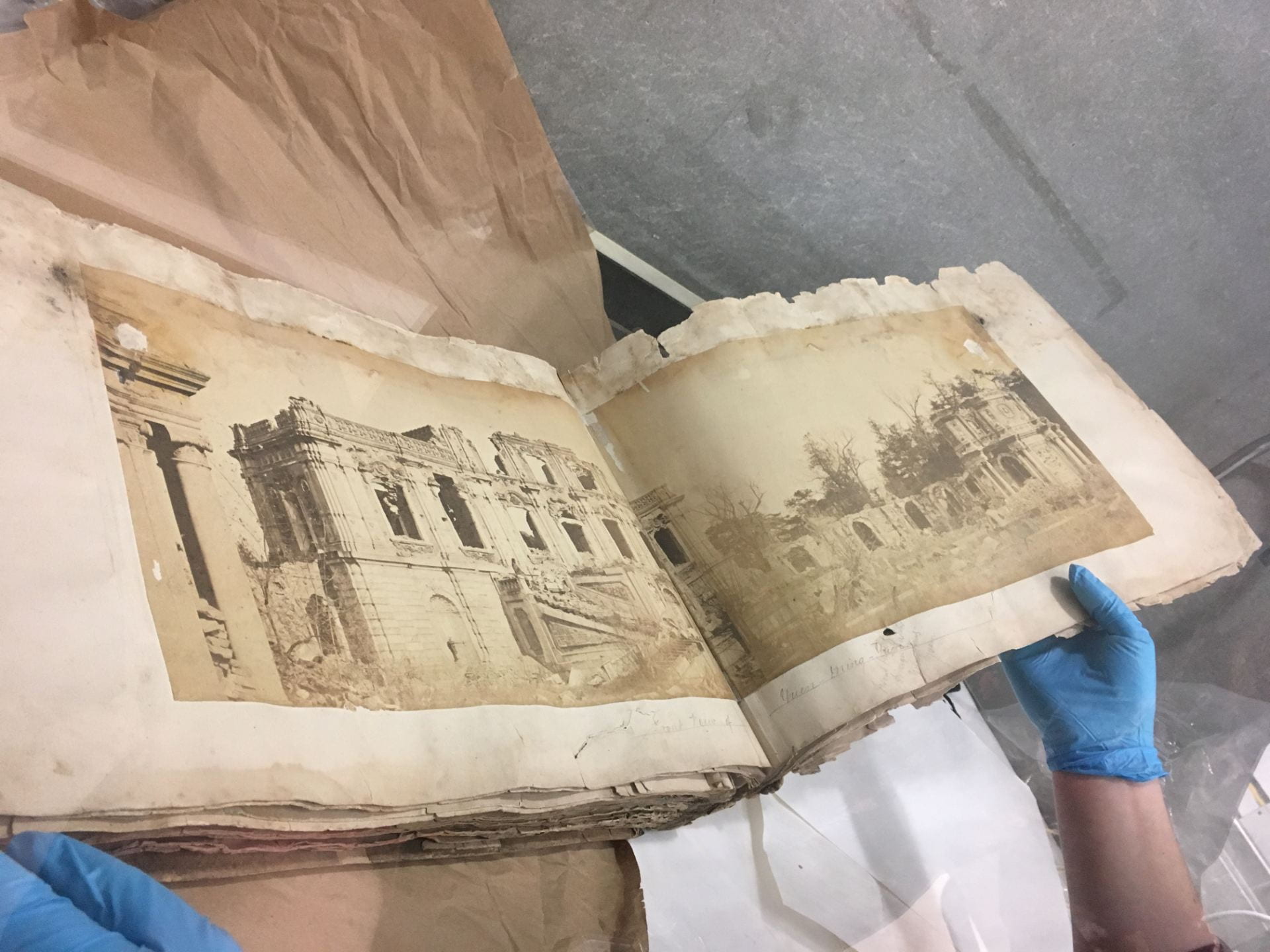

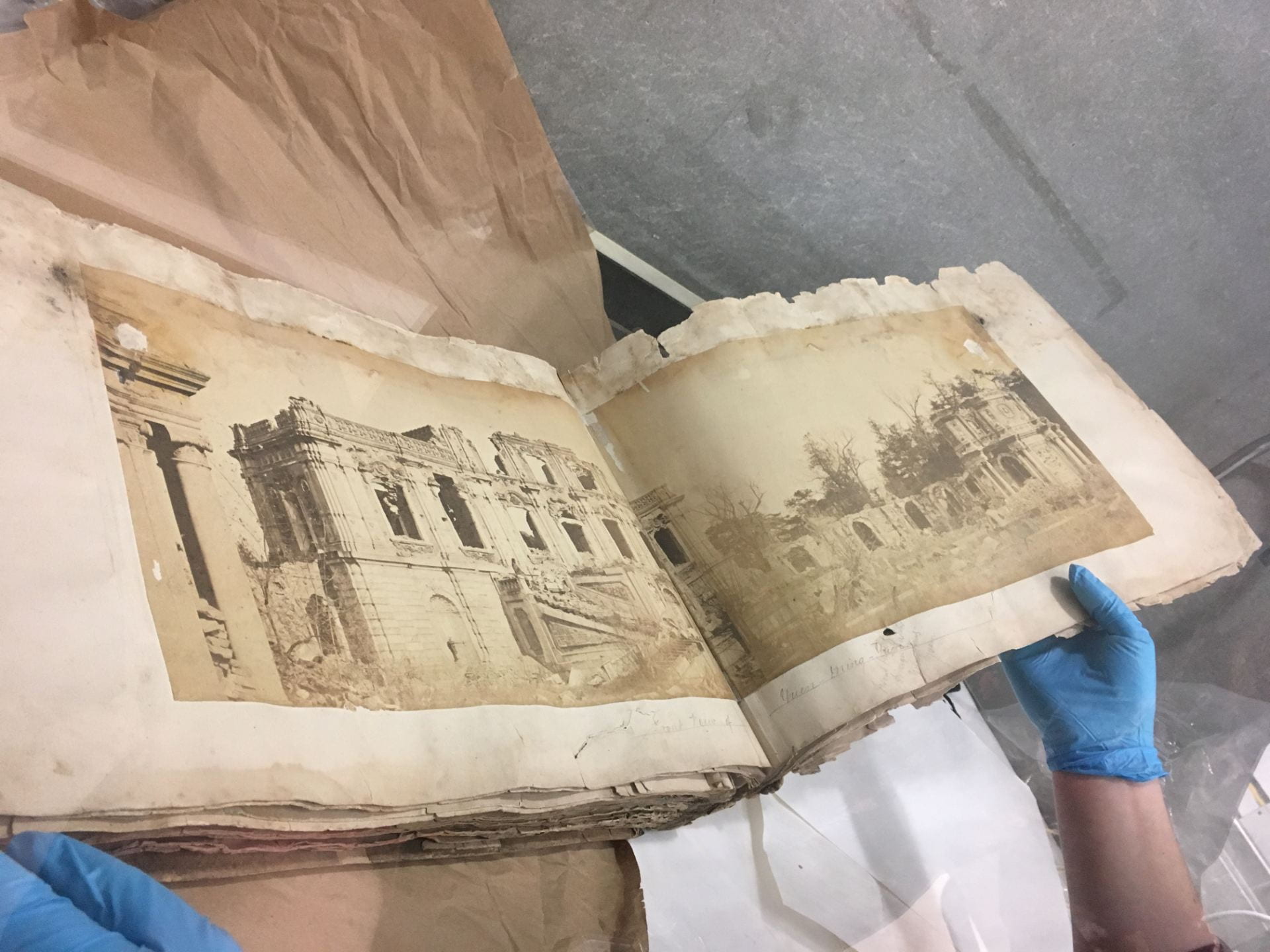

The Royal BC Museum also have an album (ref: MS-3171.1) of 155 prints among their Moore material. The album, not in the best condition, probably contains many photographs by Moore. There are therein some photographs of the ruins of the European palaces at the Yuanming Yuan (圆明园), including the following panoramic view of the burnt out shell of the Palace of the Delights of Harmony (Xieqiqu):

Two-part panorama of the ruins of the Palace of the Delights of Harmony (Xieqiqu), Yuanmingyuan (Old Summer Palace), Beijing. Photograph attributed to Charles Moore, c.1875. Image by Sally Butterfield (Archivist, Royal BC Museum) taken under a fume hood due to old mould.

In Barbarian Lens, Western Photographers of the Qianlong Emperor’s European Palaces (Gordon and Breach, 1998), Régine Thiriez speculates about a mystery/unidentified photographer and is tentative about attributions to Théophile Piry. Indeed, two images of the ruins reproduced in Barbarian Lens, which are attributed to anon, turn out to be by Moore: J-00442 at the Royal BC Museum is the negative for Fig 35 on page 58. J-00463 is the negative for Fig 47 on page 88.

Furthermore, at least four images reproduced in Terry Bennett’s book History of Photography in China Western Photographers 1861-1879 (Quaritch, 2010) are also, most probably, by Moore rather than Piry, including:

J-00413 (fig. 5.35, page 299)

J-00443 (fig. 5.36, page 300)

J-00479 (fig. 5.29, page 298)

J-00508 (fig. 5.33, page 299).

Contemporaries in the Imperial Maritime Customs, Ernst Ohlmer, Charles Moore and Thomas Child (followed by later photographers, but interestingly, not John Thomson, apparently) photographed the melancholy and evocative ruins of the ‘ravishing’ ‘fairy palaces’ and gardens [2] which had been looted and torched by Franco-British forces in 1860 at the end of the Second Opium War. Their photographic records of the devastation as it degraded can be dated: Ohlmer (c.1873), Moore (c.1875) and Child (c.1877).

Bibianne Yii (1848/49-1914) married Charles Moore at the British Legation in Beijing on 23 March 1868 and the couple went on to have eleven children. In this photograph, presumably by Charles Moore, Bibianne is said to be sitting next to her wedding headdress (Source: DeeDeeEmme, via Ancestry.com).

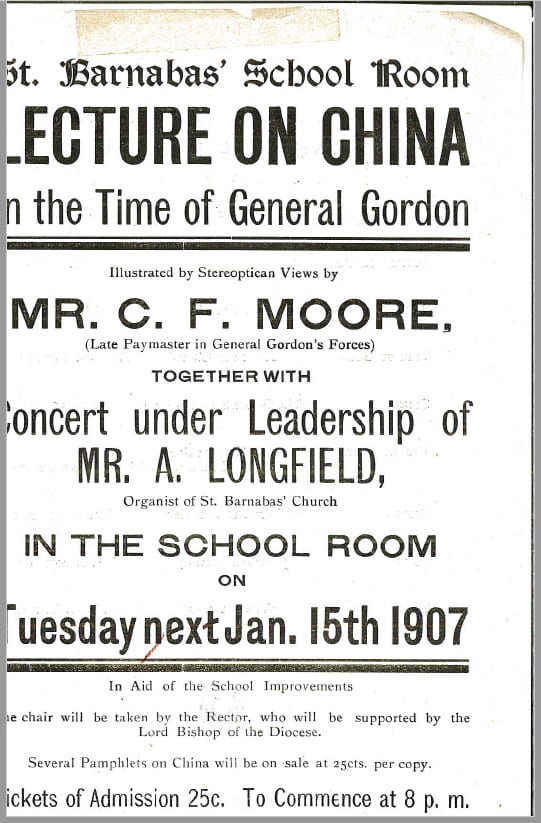

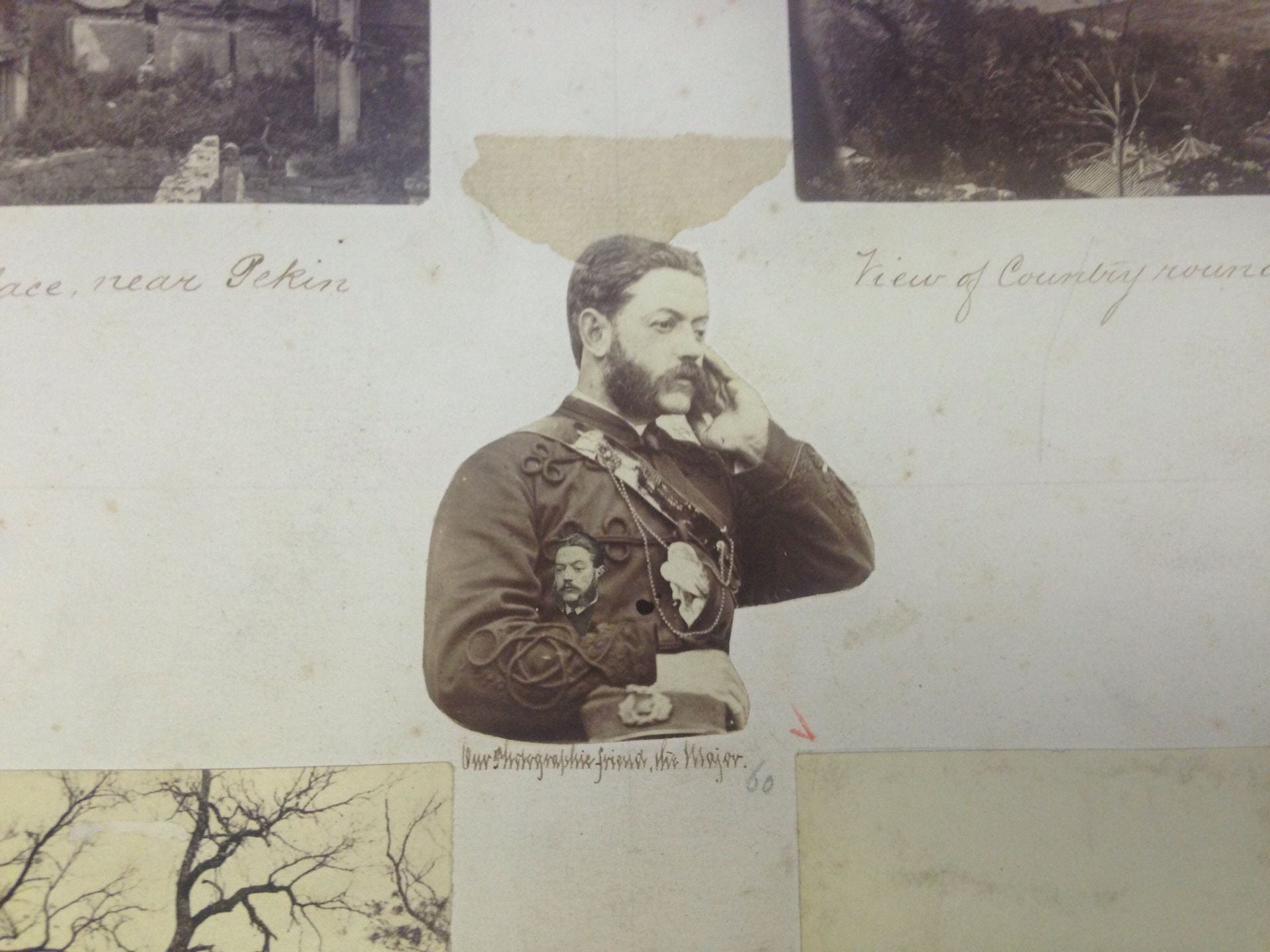

More attributions to Moore could surely be ascertained in archives and collections that have emerged recently. For example, an album sold at Bonham’s Knightsbridge on 27 March 2019, is promising. This album includes an inscription by Bibianne Moore, Charles Moore’s wife, who had presented it to Hester Hart, Sir Robert Hart’s wife. The album contains at least sixteen duplicates of prints also found in an album in the Edward Bowra Collection (HPC ref: Bo01), and nine photographs usually attributed to Dr John Dudgeon. However, given the provenance of the album, the chances are that some of the photographs in it would have been taken by Bibianne’s husband Charles. Indeed, two photographs in the Bonham’s album are almost certainly by Moore: a wooden cabinet carved by Sung Sing Cung and a carved bedstead – these photographs are listed in Moore’s 1873 ‘Catalogue of Pictures’, see below, respectively Y3 and Y2. This furniture was exhibited in Vienna in 1873; the Chinese contribution to the exhibition was organised by Edward Bowra.

The Bonham’s album also contains several photographs of Jiujiang (Kiukiang), where the Moore family were living at the time. The Jiujiang photographs may well be by Moore, including one entitled ‘Kiukiang – Bungalow’ of a modest residence (and a possible outhouse darkroom, with a useful fresh water stream nearby?), which was likely their home. It is also noted that oval shaped masks on prints (or prints then cut to an oval shape) could be a characteristic of Moore’s, although other photographers of course also made oval shaped prints.

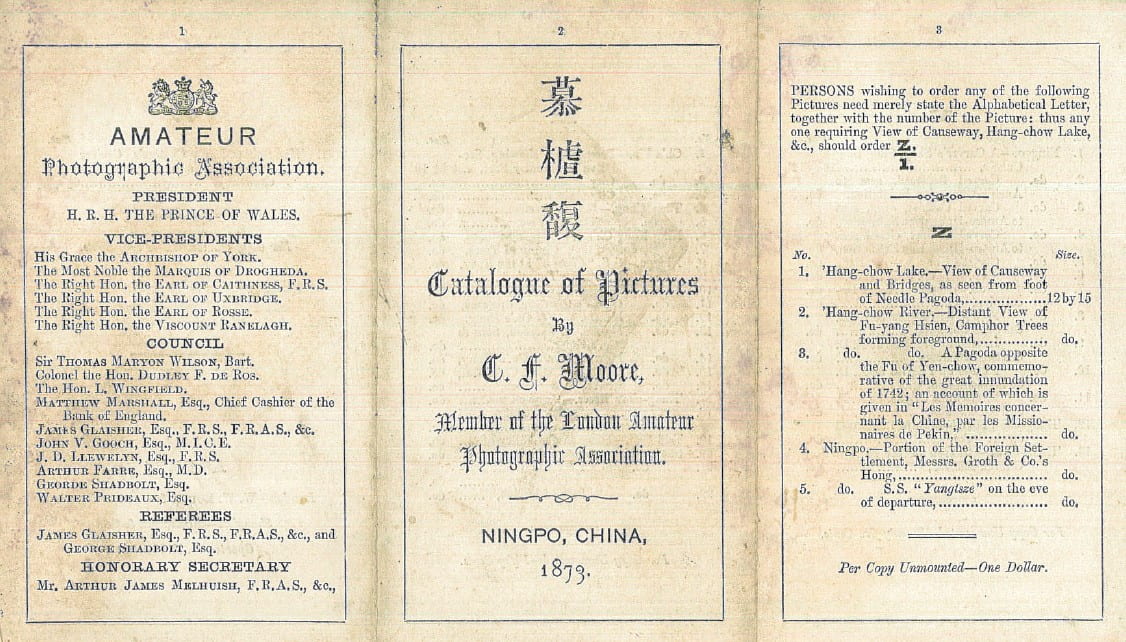

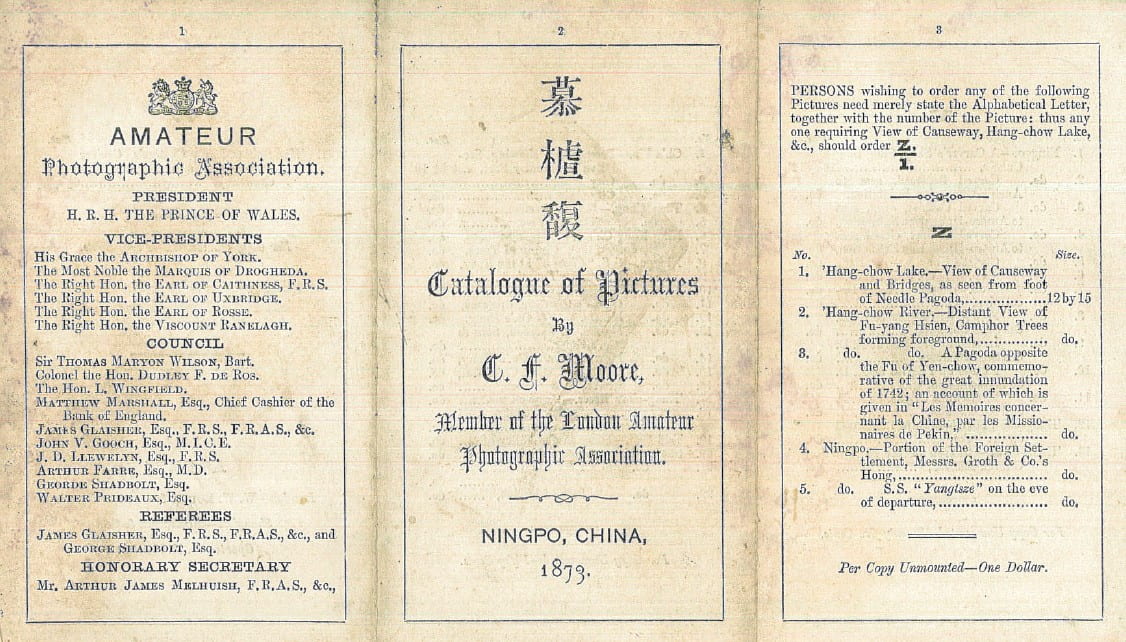

Moore lists for sale, forty-one views of Hangzhou, Ningbo and vicinity. Some of the more specific descriptions may help identify these photographs, if they still exist, as by Moore. The ‘Catalogue of Pictures by C.F. Moore’ is in the Royal BC Museum ref: MS-3172.

The photograph X1 (‘Ch’a P’u. – Promontory showing Section of Circular Fort’) listed in Moore’s 1873 catalogue is most probably Bo01-042. X2 (‘Ch’a P’u. – City Wall’) is most probably Bo01-047. X3 (‘Ch’a P’u. – City Gate’) is probably another atmospheric Moore photograph: Bo01-048. Bo01-043 can also be attributed to Moore. These four Zhapu photographs are in addition to the three Zhapu photographs by Moore, noted at the beginning of this blog. X15 (‘Custom’s Station, Chên Hai’) could well be Bo02-044.

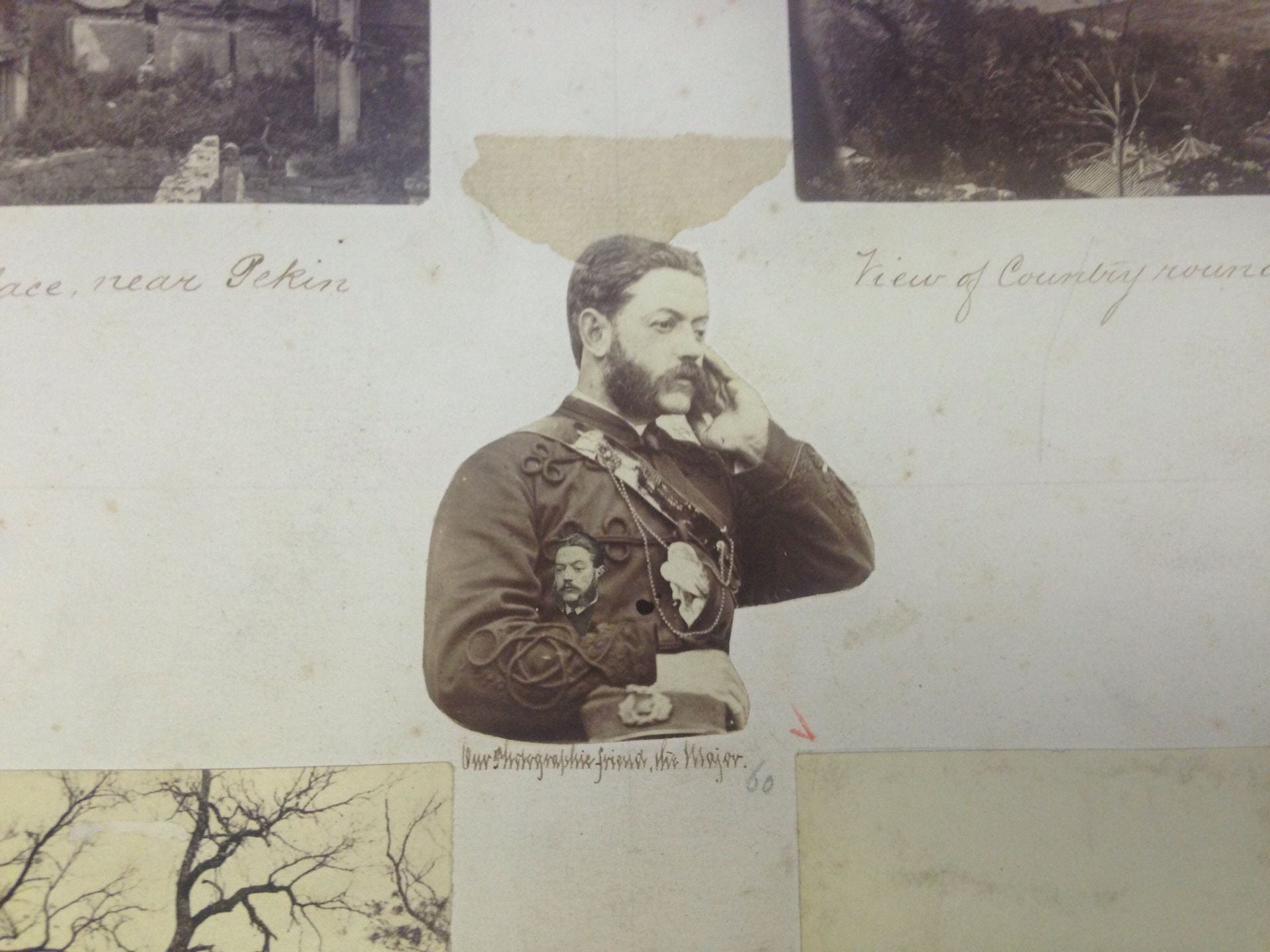

There is a further album, which will surely add to our knowledge of Charles Moore when it has been digitised and studied. The Irish Jesuit Archives (IJA) in Dublin hold an album of approximately 186 prints, housed in a wooden box inscribed with the name ‘C. F. Moore’ and ‘Pekin’. It could be the photographer’s working portfolio. The IJA archivist has pointed out that there are scribbled pencil marks beside some photographs – ‘Bad copy’, ‘Negative sold for £12.10’ (!) [3], and some shorthand notes (not unusual for Moore. His notebook for his lectures on China, see poster below, contains much shorthand). At least two of the photographs which appear in the IJA album have been reproduced and attributed to Dudgeon – attributions, which, given the context, could be revisited. [4]

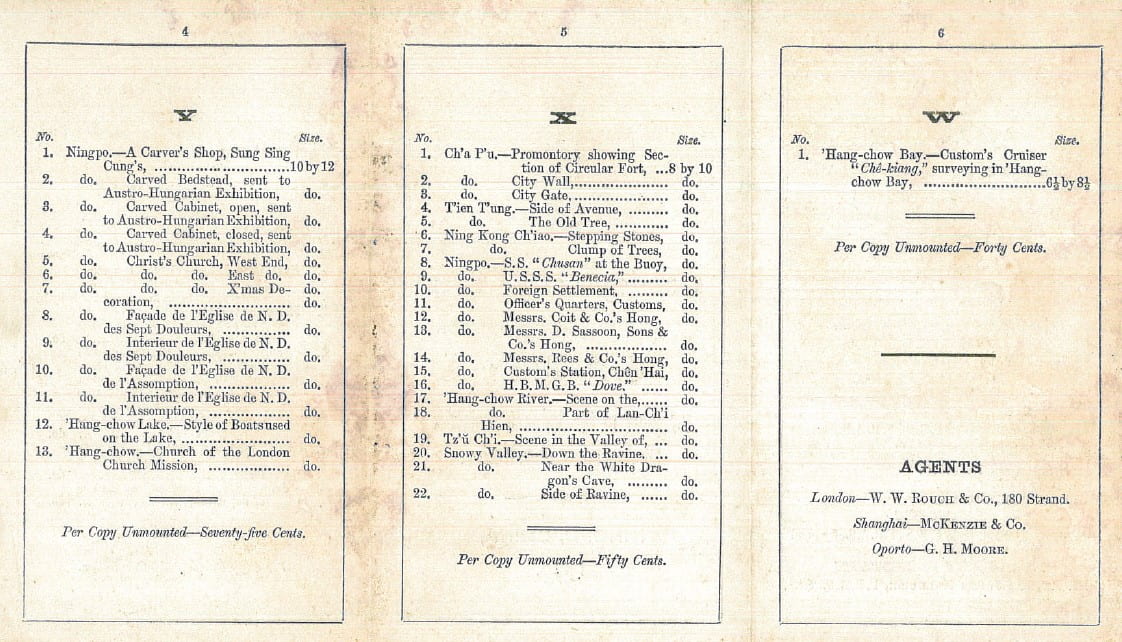

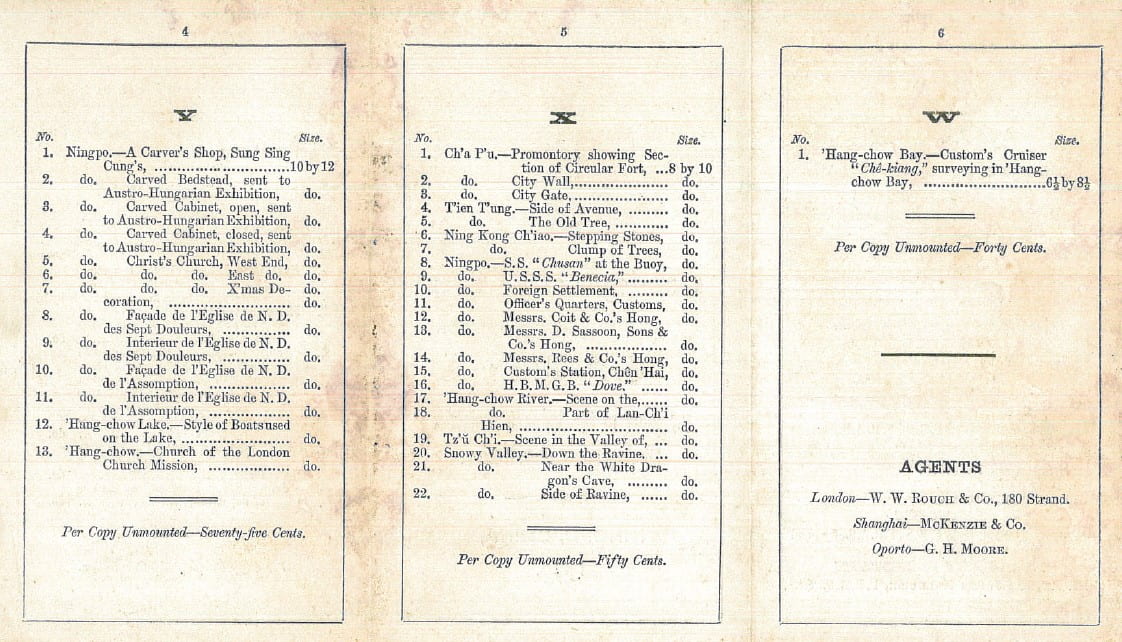

A portrait in the IJA album is captioned in the same distinctive handwriting (thought to be Charles Moore’s ‘presentation/calligraphic style’ hand) as in the Bonhams album, as follows: “Our photographic friend the Major” – i.e. Major James Crombie Watson, superintendent of police at Ningbo. Terry Bennett has noted that it seems that there was a group of photography enthusiasts in Ningbo – residents and passers through. Very likely they would often team up for outings, and take more than one camera. This would explain variants that crop up so often (a scenario possibly exemplified by Bo02-086, Bo02-087, Bo02-088 and negatives J-00460, J-00471 and J-00453 – all taken at the same place, recorded in the Bowra album as an ancient tomb near ‘Wang Chă’.

Photomontage double portrait of Major James Crombie Watson, c.1870 (See Bo02-001), holding a second portrait of himself and with someone/something in his pocket, pasted in to the album at the IJA. Image courtesy of the Irish Jesuit Archive, Dublin.

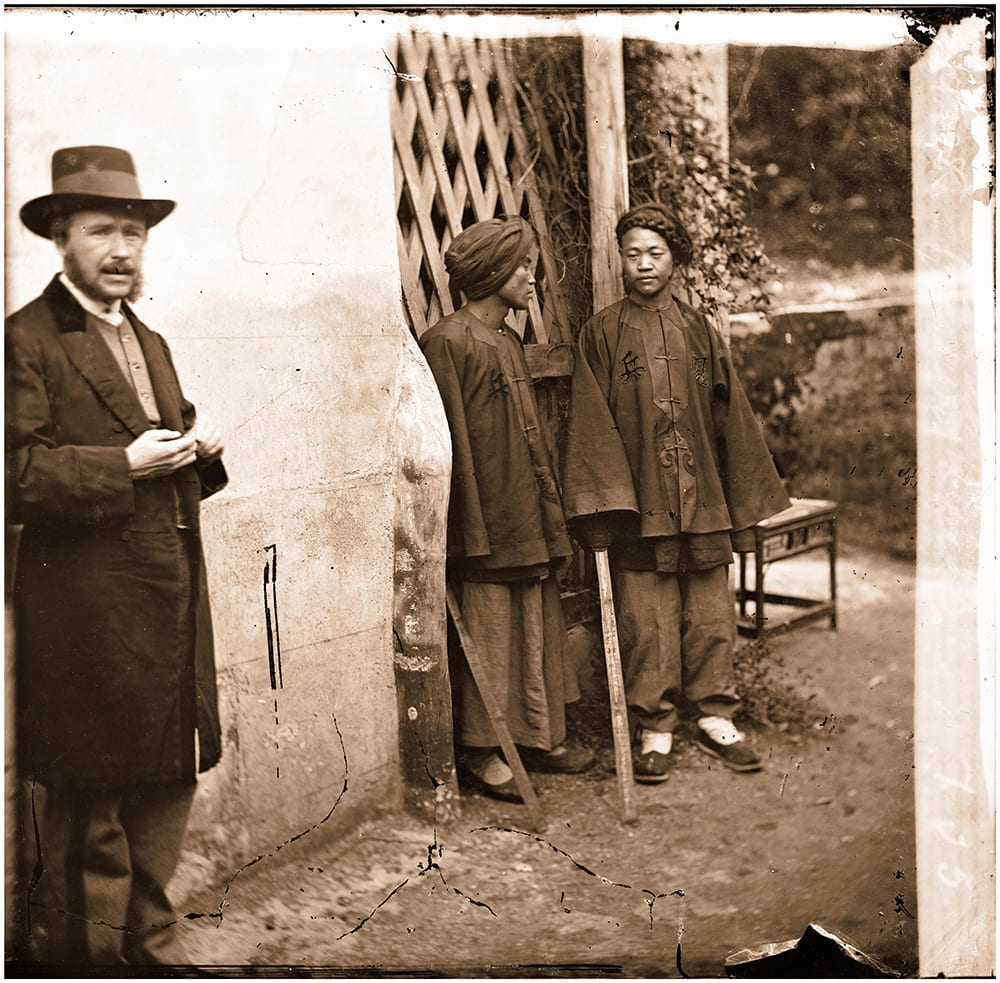

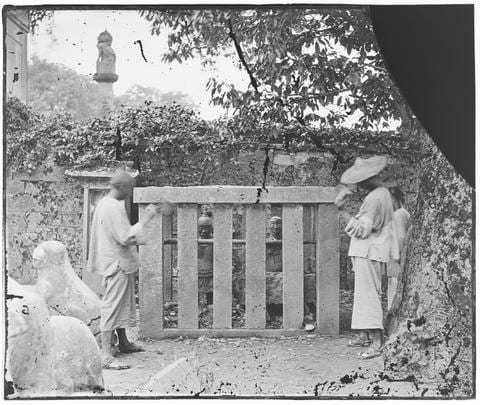

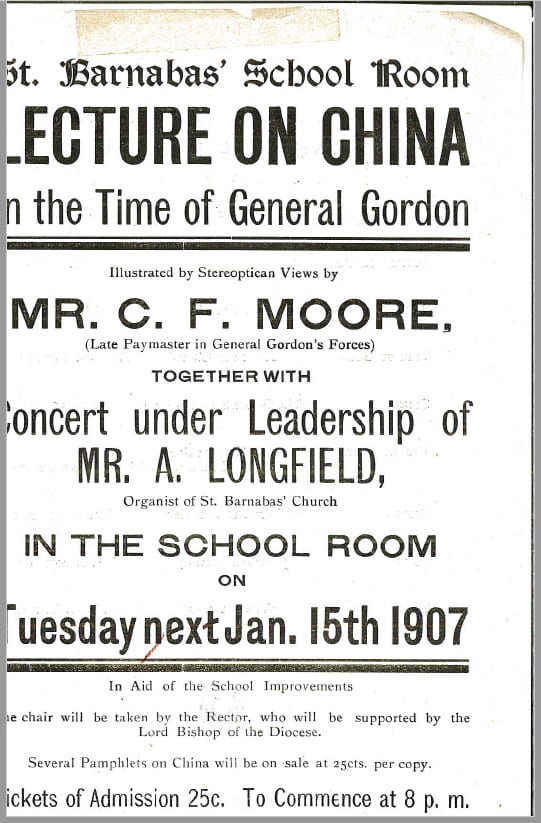

By 1873, Moore was a member of the London Amateur Photographic Association. A moot question is: had he been an active photographer earlier, when he served as paymaster with General Charles Gordon’s ‘Ever Victorious Army’? In any case, in 1907, Moore gave lectures in Canada, on ‘China in the time of General Gordon’, illustrated by ‘Stereopticon Views’ (i.e. magic lantern slides). The Moores had emigrated to British Columbia, Canada in 1885, and Charles worked there as a notary public. The Royal BC Museum also hold Moore’s lecture notebook, listing, I gather, the lantern slides projected, including the remarkable image below (negative ref no: J-00496), a set up action shot/narrative photograph, ambitious for the period, which is also a valuable historical document (Visitors to the temple nowadays are apparently asked not to spit at replicas of the figures of the murderers).

Poster for ‘China in the time of General Gordon. (Royal BC Museum ref: MS-3172).

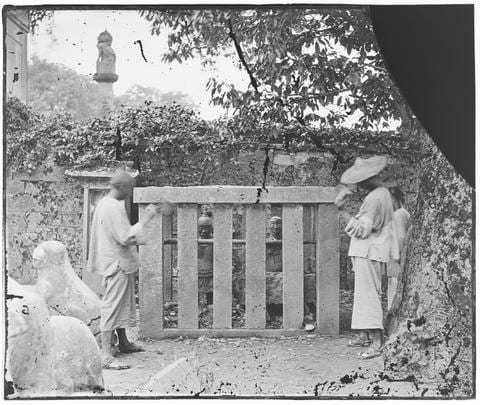

Photograph by C.F. Moore. Two men posed, seemingly throwing stones at iron figures, at Yue Fei Temple (Yuewang Temple 岳王廟), West Lake, Hangzhou, c.1870. This photograph (negative ref no: J-00496) is listed in Moore’s ‘China in the Time of General Gordon’ lecture notebook: “13. Iron figures in stone cages, being the conspirators who compassed the death of Yoh Fei, his son and family.” See Ar01-016 (note the sculpture on a column in both images).

There is a brief biography of Charles Frederick Moore here , based on a longer one here.

C.F. Moore was evidently an accomplished and significant photographer, active over diverse parts of China, for several years. It is marvellous to think of Moore’s ‘ingeniously contrived’ sedan chair darkroom, carried hither and thither by patient porters – the Chinese equivalent of Roger Fenton’s ‘Photographic Van’ in the Crimea. Further research, including into the albums, negatives and associated papers mentioned above, and into Moore’s career in China, will cast more light on his importance as a photographer in China, hitherto underappreciated.

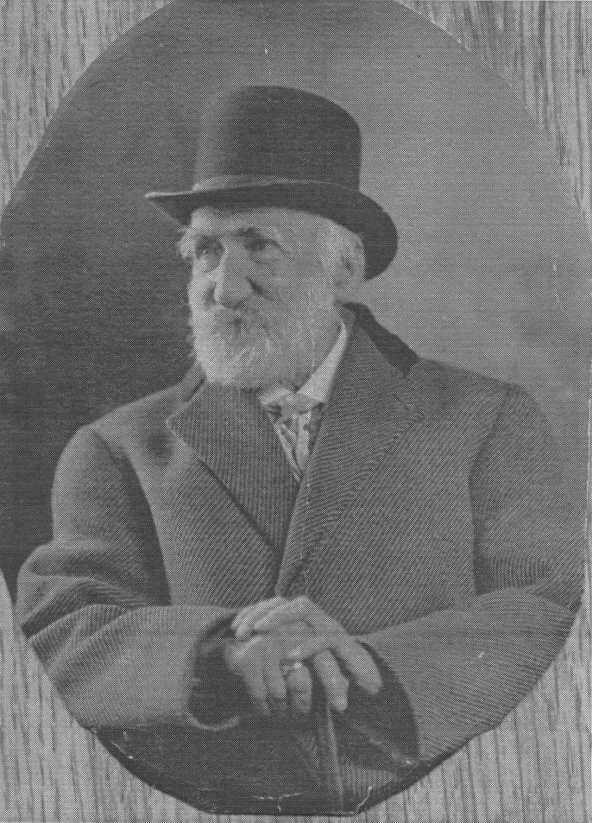

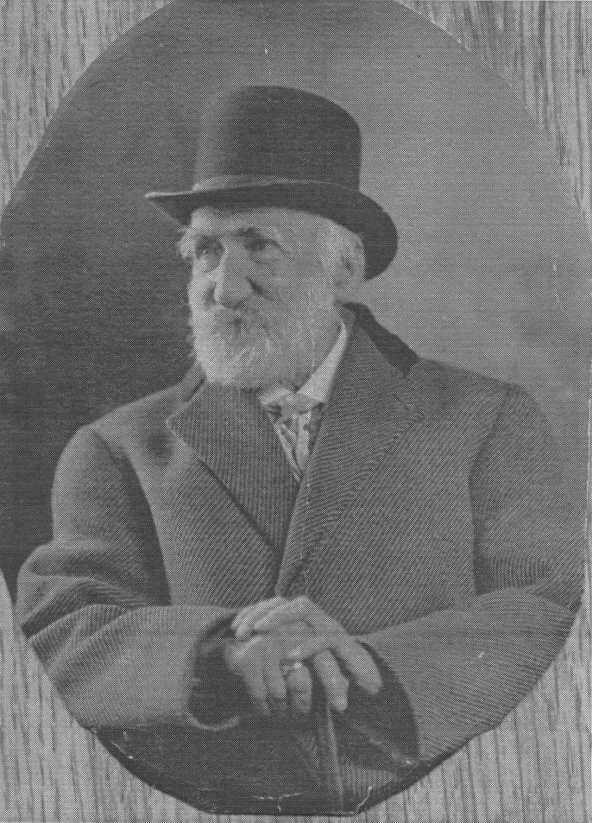

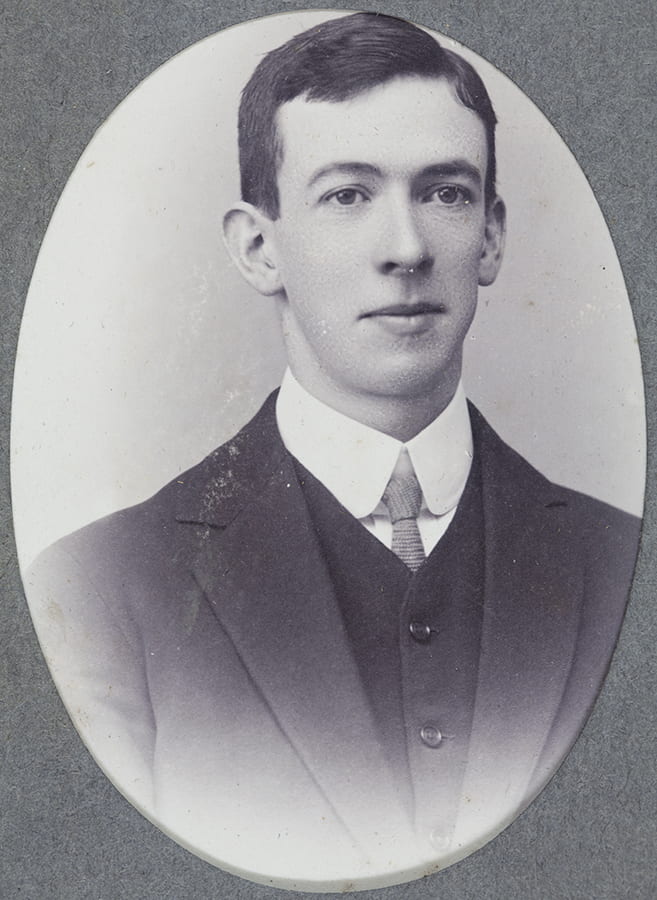

This is thought to be a portrait of Charles Frederick Moore, taken in British Columbia, Canada, c.1910 (Source: DeeDeeEmme, via Ancestry.com). This is thought to be a portrait of Charles Frederick Moore, taken in British Columbia, Canada, c.1910 (Source: DeeDeeEmme, via Ancestry.com). CORRECTION (7 May 2023): This image is a greyscale copy of a portrait photograph of Charles Frederick Moore (1837-1916), held at the Royal BC Museum, Victoria BC, Canada (ref: MS-3172).

Footnotes

[1] Quoted in Letters of Sir Thomas Hanbury (1913), page 218. Letter dated 31 October 1870. Dr Andrew Hillier kindly sent me this extract, for interest.

[2]Barbarian Lens, Western Photographers of the Qianlong Emperor’s European Palaces by Régine Thiriez (Gordon and Breach, 1998), page 92.

[3] Attributing nineteenth century photographs taken in China is notoriously difficult, complicated by the selling of negatives (cf. ‘The Firm’). Prints circulated between friends, and among photographers. Prints shared with the recipient’s name written on the back can be a red herring.

[4] The photograph in the IJA album captioned “161. The Bell Tower French Legation – Montbelle, Rochechouart, Champes” is surely Fig. 2.11 on page 44 of Terry Bennett’s History of Photography in China Western Photographers 1861-1879 (Quaritch, 2010). Another photograph in the same album which is captioned “176. Students British Legation, Pekin – Bristow, Andrews, Ford, Hillier[s], Scott, Baber, Margary, McKean, Carles” must be Fig. 2.23 on page 55, ibid. Both of these photographs are currently attributed to Dr John Dudgeon.

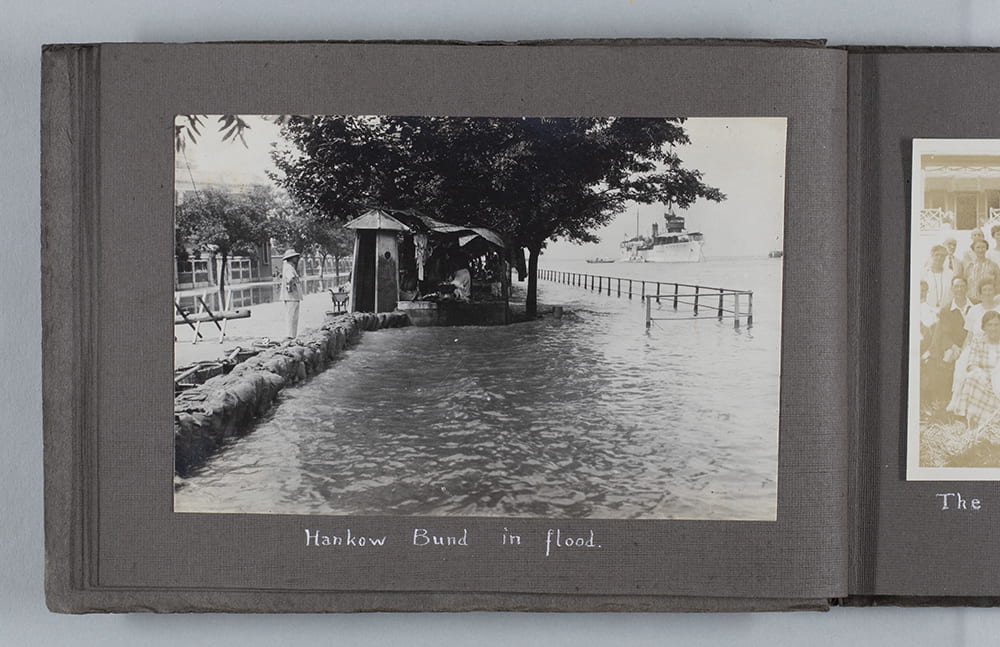

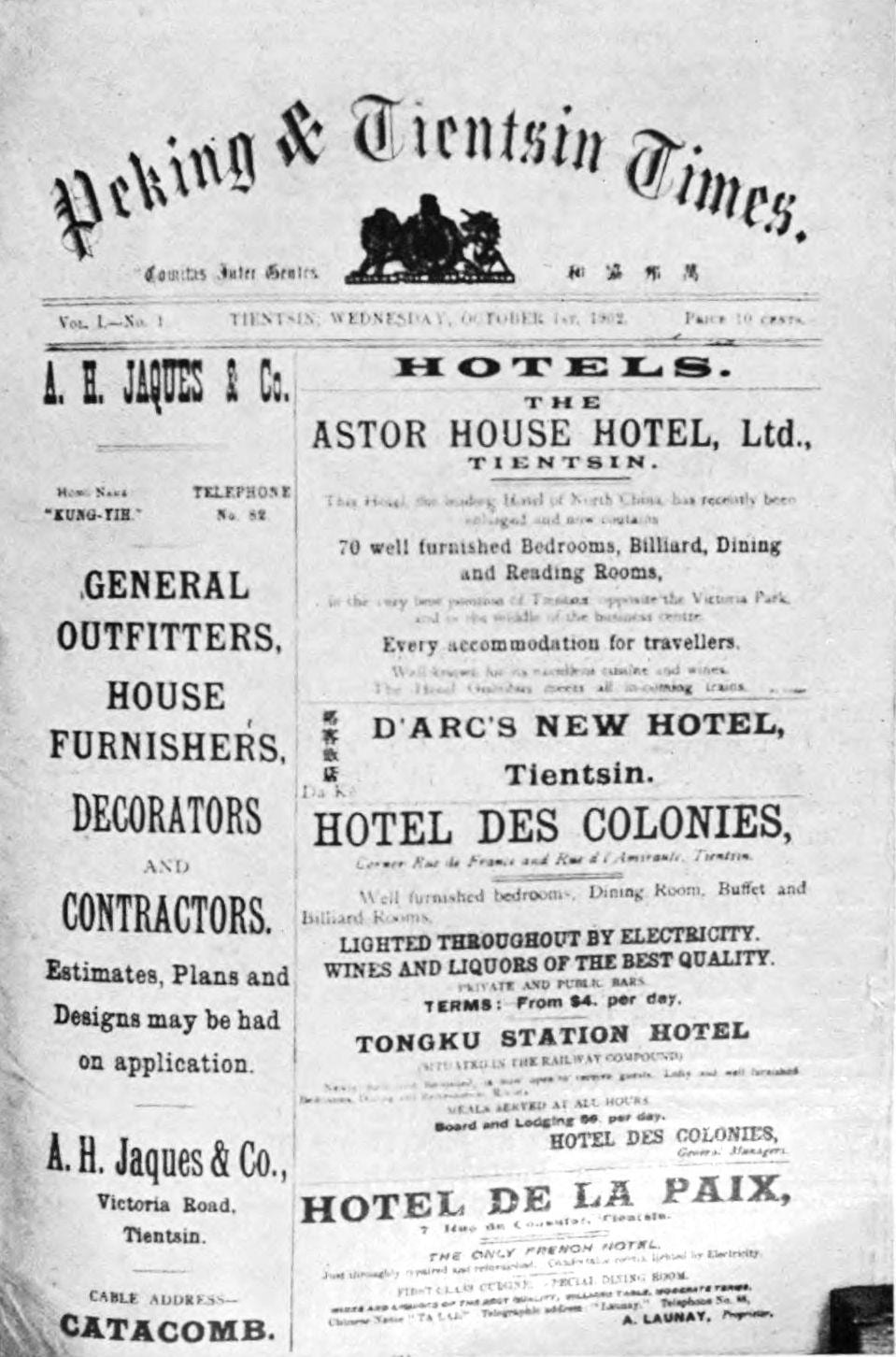

Woodhead appeared all-powerful in Tianjin between the world wars, though he did have some competition. The North China Commerce newspaper was established in 1920 as an English-run weekly but didn’t last long while the American-owned North China Star was also published in Tianjin. This was real competition – the American State Department estimated the paper’s daily circulation in 1921 as 2,500, more than double Woodhead’s Peking and Tientsin Times, but also noted that the Star was far less influential than Woodhead’s paper which to men like Woodhead was what really counted.

Woodhead appeared all-powerful in Tianjin between the world wars, though he did have some competition. The North China Commerce newspaper was established in 1920 as an English-run weekly but didn’t last long while the American-owned North China Star was also published in Tianjin. This was real competition – the American State Department estimated the paper’s daily circulation in 1921 as 2,500, more than double Woodhead’s Peking and Tientsin Times, but also noted that the Star was far less influential than Woodhead’s paper which to men like Woodhead was what really counted.